The child’s natural process

Nature equips the child with the ability to accomplish amazing things in their early years. They learn to walk, talk, and otherwise navigate a very complex environment.

We don’t directly “teach” them how to accomplish all this. They seem to have their own build-in way of doing it.

But we do need to intervene more directly with reading and writing. So to figure out how to best do that, we look now at how they accomplished so much in their early years.

As we begin, it’s immediately obvious that —

A child comes into the world already equipped with both the strong desire and ability to copy what they see us doing.

Exactly how a child does this remains hidden to us.

But we can certainly see the outward effects of their process as it unfolds. And looking carefully at it, we can draw some conclusions about how to help them later.

So that’s where we begin here — looking first at how they learn to walk.

Learning to Walk

First, consider walking. Obviously, the newborn doesn’t go directly from lying in the crib to walking. But while the exact manner differs, they take a similar sequential path.

Over time, they turn over, sit up, creep, crawl, stand, take a few steps while holding on — and eventually walk on their own.

From this, we can see they progress along a path through a series of stages, each a little more complex than the one before.

We can also see we don’t “teach” the infant to walk. But we do provide a safe, supportive environment. Safe in that we make sure they don’t fall over a ledge or get into something harmful.

Supportive, in that we provide enough space that they are’t confined, give them our hand when they need it, and express our genuine pleasure as they proceed.

Think of learning to write and read as following along a path of increasingly complex stages, too, as we provide a safe, supportive environment.

Learning to Talk

Now recall how a child learns to talk. Again we don’t directly “teach” them. That is, we don’t sit them in their high chair and demonstrate how to say the words we have decided they should focus on that day.

We don’t break the words down into separate sounds, then describe how the child should place their tongue just so and use their breath in certain ways to make those sounds.

Instead, while we are carrying out some “real life” activity with special meaning for the child, we model the words associated with it.

For instance, if a cat comes into the room, we may pet it, saying things like, “Hello Kitty!.. Let’s pet the kitty… Be gentle with the kitty… Good Kitty…” and so on.

For instance, if a cat comes into the room, we may pet it, saying things like, “Hello Kitty!.. Let’s pet the kitty… Be gentle with the kitty… Good Kitty…” and so on.

After a few times of this, the child will excitedly call out “Keee, keee!” when the cat appears. Eventually one day, we hear them clearly say, “Kitty!”

In response, we probably smile and say something like, “Yes, here comes the kitty!”

Exactly how the child accomplishes this — and so much else — remains a mystery to us. And we don’t need to know.

What we do need to know and to trust is that — barring some extreme physical barrier — they can and will continue to develop the ability to speak as we model for them in this way.

So for our purposes here, we can note that we don’t “teach” a child to talk, in the direct, traditional sense, but —

We help a child learn to speak by using words with strong meaning for that child — while in a “real life” situation.

Scribbling: A significant Clue

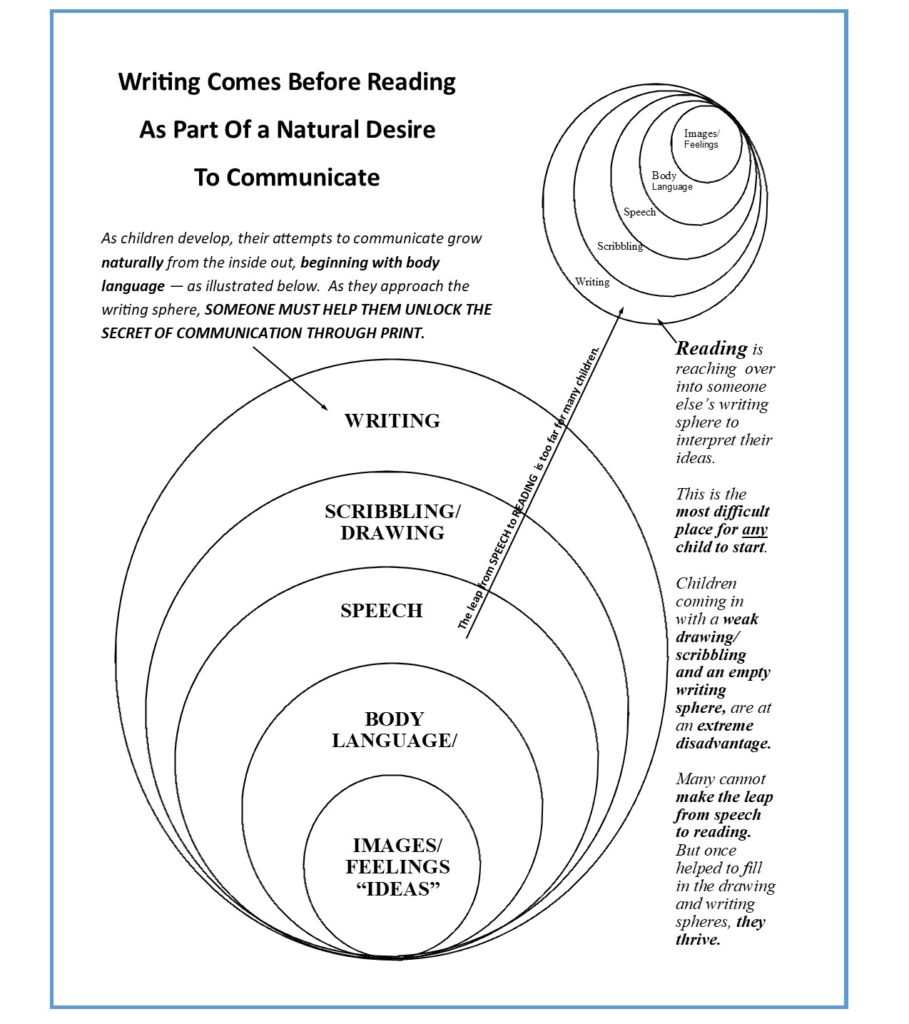

Once the child can speak fluently, our challenge is to decide what comes next. That is, what’s the best way — the safest way — to help them move from speech into print?

Here we can look at how a child who’s been immersed in a print-rich environment in their early years responds to the print they see around them. What does such a child do if left to their own devices?

What we find is that having been read to and watched others write, they will begin to see the connection between speech and print.

And in a print-rich environment, they will also, no doubt, have access to something akin to pencil and paper. So in an attempt to copy some of what they’ve seen others doing, they will start Scribbling and Drawing.

One day they make indiscernible marks on their paper, look up proudly and say something like, “See, this is our kitty, and here’s where it says ‘Kitty.’”

With this they are showing us they now realize print is used to convey ideas/speech —and they want to do it themselves.

Scribbling is one of the most valuable clues the child gives us. For this tells us that —

As the child grows, they continue to strive to communicate what’s at their center. So once they can speak, the next challenge they want to take on is translating that speech into print.1

If we combine this with the realization that they most readily copy what has strong meaning for them, we can devise practical strategies for an approach that’s “natural” for the child.

Doing that over the years, I have found that a child will progress through 5 increasingly complex stages toward reading books.

So let’s look next at the child’s natural path.

5 Stages in A child’s natural Path toward reading

From birth forward, the child is intent on communicating what’s at their center.

As an infant, they convey their feelings through Crying and various forms of Body Language. Before long, they begin to develop Speech.

Virtually all children make it this far.

If in a print-rich environment, they will begin to Scribble. And it’s here that we need to intervene, to model how to translate their own speech into print.

With this modeling, a child continues, ultimately working through the following 5 stages:

1. Crying/Body language –>

2. Speech –>

3. Scribbling/Drawing –>

4. Writing —>

5. Reading Books

The child proceeds along this path propelled by their desire to communicate what’s on their mind. So the last stage for the child is Reading Books2 written by someone else.

This, as such books represent what’s on someone else’s mind — or perhaps what an author thinks might be on a child’s mind.

It’s important to note that distinction: The child’s natural path toward reading ends with reading books others have written. It doesn’t begin there.

What if a child is asked to skip writing?

Deciding3 to move a child from Speech directly into Reading Books, interrupts their natural process, making any child’s progress more difficult. Here’s how it can affect children from different home/preschool environments:

A. Child from a print-rich environment: These children have probably already reached the Scribbling/Drawing stage. But most have not yet moved into Writing — so here’s how the challenge looks for them:

1.Crying/body language –> 2.Speech –> 3.Scribbling/Drawing –> 4.Writing —> 5. Reading Books

When faced with a reading program that skips writing — one which begins with basal readers or by focusing on phonics, then phonics books — some may struggle a bit, perhaps a great deal. Yet it’s likely they will ultimately bridge the gap.

B. Child NOT from a print-rich environment: These children have stopped at Speech. So by skipping writing, the challenge for them looks something like this:

1.Crying/body language –> 2.Speech –> 3.Scribbling/Drawing –> 4.Writing —> 5. Reading Books

Too many of these children struggle, even completely fail to make the leap. This affects them in school and far beyond. And it is completely unnecessary.

For a child who has not yet gone beyond Speech need not be at such a strong disadvantage. For if we show them how their own words look in print, they quickly come to realize print is “talk written down” and move steadily forward.

All children can be successful, as long as they all have similar modeling from us. Some will just need a little more time.. So —

Each child needs to progress at their own pace. And that’s why we provide an individualized, natural approach.

Following is a brief description of the practical strategies within this approach.

Key Words: at the heart of an Individualized, natural approach

Keeping in mind how important hearing words with strong meaning was for the child learning to speak, we now use a similar strategy. That is, we model how their own speech must be written, if others are to readily understand it.

We do this by writing for them one special word each day — a word they ask for after telling us why it’s so important to them. This is their “Key Word” for the day.

So for instance, they are telling us how much they like ice cream. They talk about the last time they had an ice cream cone, how it dripped down on their hand holding the cone, what flavor

So for instance, they are telling us how much they like ice cream. They talk about the last time they had an ice cream cone, how it dripped down on their hand holding the cone, what flavor  they especially like, etc. Eventually we write “ice cream” on a sturdy “word card” for them. They punch a hole in the card and place it on their metal “word ring.”

they especially like, etc. Eventually we write “ice cream” on a sturdy “word card” for them. They punch a hole in the card and place it on their metal “word ring.”

This is today’s Key Word for that child.

We also give them a duplicate of the word card — this one on newsprint. Their follow-up activity is to draw a picture about that day’s word in their writing book and paste the duplicate under their drawing.

Virtually always, they will recognize this word the next day, because it has special meaning for them. Also, they focused on it for quite awhile that previous day, so it “sticks.”

Forgetting yesterday’s word very seldom happens. But in that rare case, we take the word off the ring and talk a little longer to be sure they’re thinking of something with strong meaning for them.

We’re especially careful about this. For we want them to have a collection of words that gives them not only practice, but confidence with print.

Note that at this point, they are remembering/recognizing words, more than what we usually think of as reading. But reading, in the traditional sense, is not far away.

For as you will soon see, we will provide a structure to ensure their progress toward that goal.

Incorporating phonics, letter formation and more into Key Words

As we write their special word day after day — we also say the letters and/or make the sounds as we write. We do this incidentally, not in a way that interrupts the writing process. With this, just as they did with speech, the child begins to absorb the connections.

So in this way, we incorporate phonics into this process from the very beginning. And we expand on it with their need to spell, once they are writing independently.

They also trace over the letters in the key word we print for them during each session. So they begin to learn how to form letters, use simple punctuation, and see when capital letters are needed.

Before long, they will have absorbed enough information and honed enough motor skill to move comfortably into the next stage: Writing.

By the time they can write independently, they have been reading back their own work, as well as noticing the same words appearing in the writing of others. They have a sound foundation in phonics, know how to spell the common “connecting” words and some of the other words that just need to be memorized.

By the time they can write independently, they have been reading back their own work, as well as noticing the same words appearing in the writing of others. They have a sound foundation in phonics, know how to spell the common “connecting” words and some of the other words that just need to be memorized.

From this, they have gained virtually all the skills that go into reading, so that they can move comfortably into Reading (professionally published) Books.4

To the casual observer, it’s as if reading has spontaneously emerged from the writing process. And some children will actually think they “just happened” to learn to read.

But the ability to read books others have written did not “just happen.” We very carefully orchestrated it through a structure we refer to as The Steps.5

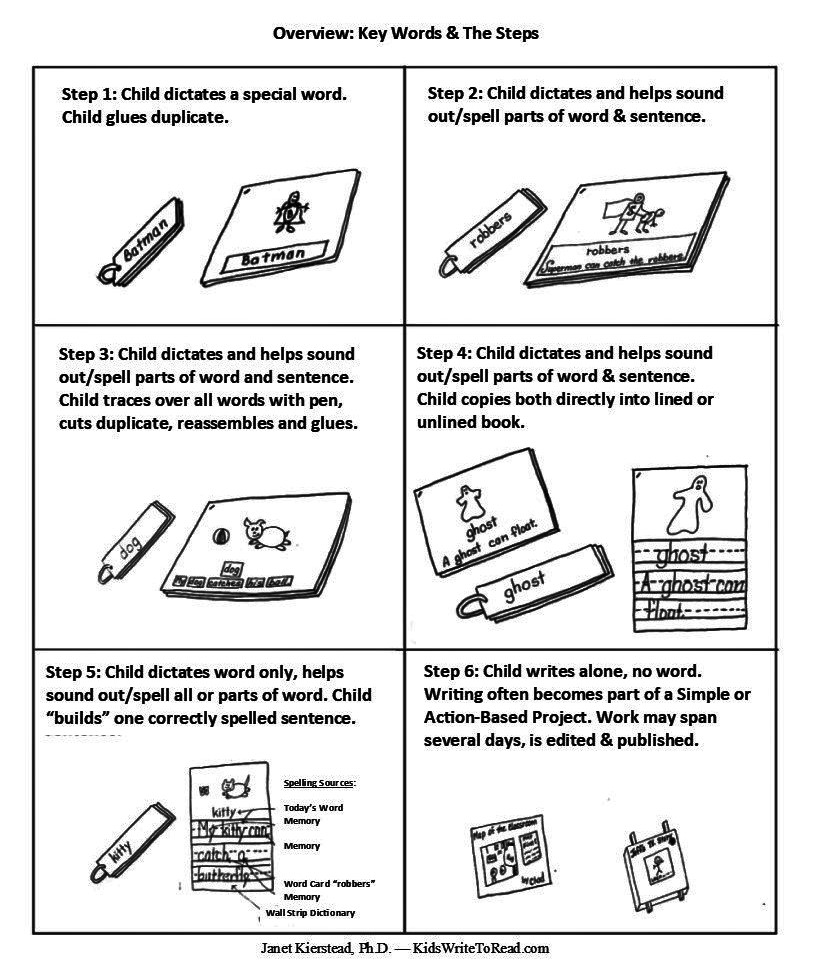

The Steps: a Structure to ensure success with writing, then reading

As the child progresses at their own pace, the follow-up activity they do with their Key Word changes. Much as they did when they learned to walk, the child works their way through a series of increasingly complex follow-up activities, referred to as The Steps.

The Steps emerged as I responded to the growth of the children in my own K-2 classroom.

As a child moves forward through these Steps, it’s important their process be challenging enough to be novel and interesting, but not too difficult. So built into The Steps is a set of criteria, provided at the bottom of this page. The adult guiding them uses these criteria to decide when a child is ready to move forward. So —

The Steps, along with Key Words, allow the child to progress at their own pace through an individualized, fail-safe, child-friendly process.

Here’s what a child is doing at each of The Steps:

Another benefit to taking a path through writing

Not only does moving through writing make the process easier for the child. But also notice that it broadens the final outcome. For —

moving in this direction

There is no “one right way” to help a child move forward along their natural path. But Key Words and The Steps are effective strategies for doing it.

I developed them when working with children in my own K-2 classroom in southern California. Some were the children of migrant farm workers. Others were the children of the land owners or professionals who chose country living over the larger towns nearby.

So the strategies are time-tested, with children from vastly different backgrounds.

These strategies are offered here as an approach for others to adopt– or as a starting place for developing their own effective strategies. I have also created the website, KidsWriteToRead.com. It describes all this in greater detail.

It also includes other components needed to support this approach — especially in the classroom: Details about phonics, moving into books, managing the active classroom, some math, and more.

Invitation to join the facebook group: helping all kids write to read

If you are in an area where a more traditional approach to reading is the common practice, you may find yourself needing some encouragement and practical support to make a different choice. I know I did.

So to provide both practical help and moral support, I have established a Facebook Group: Helping ALL Kids Write to Read: https://www.facebook.com/groups/450288968924872/ Please join us!

If you’re already a member, then please use the group to ask questions, share problems, make comments — anything you need to help you move in this direction. Also keep in mind that sharing your own work can help others.

The more we work together on this — the more children we will reach!

__________

1. Montessori also found children began to write, before reading — at around 4 years old.

2. The term “Reading Books” refers to the “cold” reading of professionally published books. But in fact, the child as been “reading” long before this. First, we have been reading nursery rhymes and children’s books to them early and often — with them sitting beside us, perhaps repeating some of what we read, singing with us, and helping us turn the pages. But on their own, they have also learned to read people’s expressions, body language and intonation. They have been reading/recognizing labels and the writing on their cereal box, and so forth. Read more about the complexity of reading.

3. For more about this decision, see the subheading, First Consider: Are We Teaching Reading Or Are We Helping the Child Learn To Read? on the page, Key Words & The Steps.

4. Read how once a child is writing their own thoughts, we move them into professionally published books.

5. This is my adaptation of Key Vocabulary, developed by Sylvia Ashton-Warner. A detailed practical description on the page Key Words & The Steps. “The Steps” are follow-up activities I devised for Key Words. The website, KidsWriteToRead.com also includes more about phonics, classroom management, some math, and virtually all other aspects of a natural approach.

Here’s another way to envision the child’s natural path:

next —> Basics for parents and teachers

< — back How a Natural Approach was developed

Questions/Comments: KidsWriteToRead@yahoo.com