The child’s natural process

Nature equips the child with the ability to accomplish amazing things in their early years. They learn to walk, talk, and otherwise navigate a very complex environment.

We don’t directly “teach” them how to accomplish all this. They seem to have their own build-in, “natural” way of doing it.

But we do need to intervene more directly with reading and writing. So to figure out how to best do that, we look now at how they accomplished so much in their early years.

As we begin, it’s immediately obvious that —

A child comes into the world already equipped with both the strong desire and ability to copy what they see us doing.

Exactly how a child does this remains hidden to us.

Exactly how a child does this remains hidden to us.

But we can certainly see the outward effects of their process as it unfolds. And looking carefully at it, we can draw some conclusions about how to help them later.

So that’s where we begin here — looking first at how they learn to talk.

Learning to Talk

Think back to how a child learns to talk. We don’t directly “teach” them. That is, we don’t sit them in their high chair and demonstrate how to say the words we have decided they should focus on that day.

We don’t break the words down into separate sounds, then describe how the child should place their tongue just so and use their breath in certain ways to make those sounds.

Instead, while we are carrying out some “real life” activity with special meaning for the child, we model the words associated with it. They child watches, listens, and apparently effortlessly absorbs what they see and hear us doing if they are interested in it.

Instead, while we are carrying out some “real life” activity with special meaning for the child, we model the words associated with it. They child watches, listens, and apparently effortlessly absorbs what they see and hear us doing if they are interested in it.

For instance, if a cat comes into the room, we may pet it, saying things like, “Hello Kitty!.. Let’s pet the kitty… Be gentle with the kitty… Good Kitty…” and so on.

After a few times of this, the child will excitedly call out “Keee, keee!” when the cat appears. Eventually one day, we hear them clearly say, “Kitty!”

In response, we probably smile and say something like, “Yes, here comes the kitty!”

Exactly how the child accomplishes this — and so much else — remains a mystery to us. And we don’t need to know.

What we do need to know and to trust is that — barring some extreme physical barrier — they can and will continue to develop the ability to speak as we model for them in this way.

So for our purposes here, we can note that we don’t “teach” a child to talk, in the direct, traditional sense, but —

We help a child learn to speak by emphasizing words with strong meaning for that child — words associated with something they’re very interested in — while in a “real life” situation.

Scribbling: A significant Clue

Once the child can speak fluently, our challenge is to decide what comes next. That is, what’s the best way — the safest way — to help them move from speech into print? For while some children do figure it out for themselves, for most, we do need to intervene.

Here we can look at how a child who’s been immersed in a print-rich environment in their early years responds to the print they see around them. What does such a child do if left to their own devices?

What we find is that having been read to and watched others write, they will begin to see the connection between speech and print.

And in a print-rich environment, they will also, no doubt, have access to pencil and paper. So in an attempt to copy some of what they’ve seen others doing, they will start Scribbling and Drawing.

One day they make indiscernible marks on their paper, look up proudly and say something like, “See, this is our kitty, and here’s where it says ‘Fluffy.’”

With this they are showing us they now realize print is used to convey ideas/speech —and they want to do it themselves.

Scribbling is one of the most valuable clues the child gives us. For this tells us that —

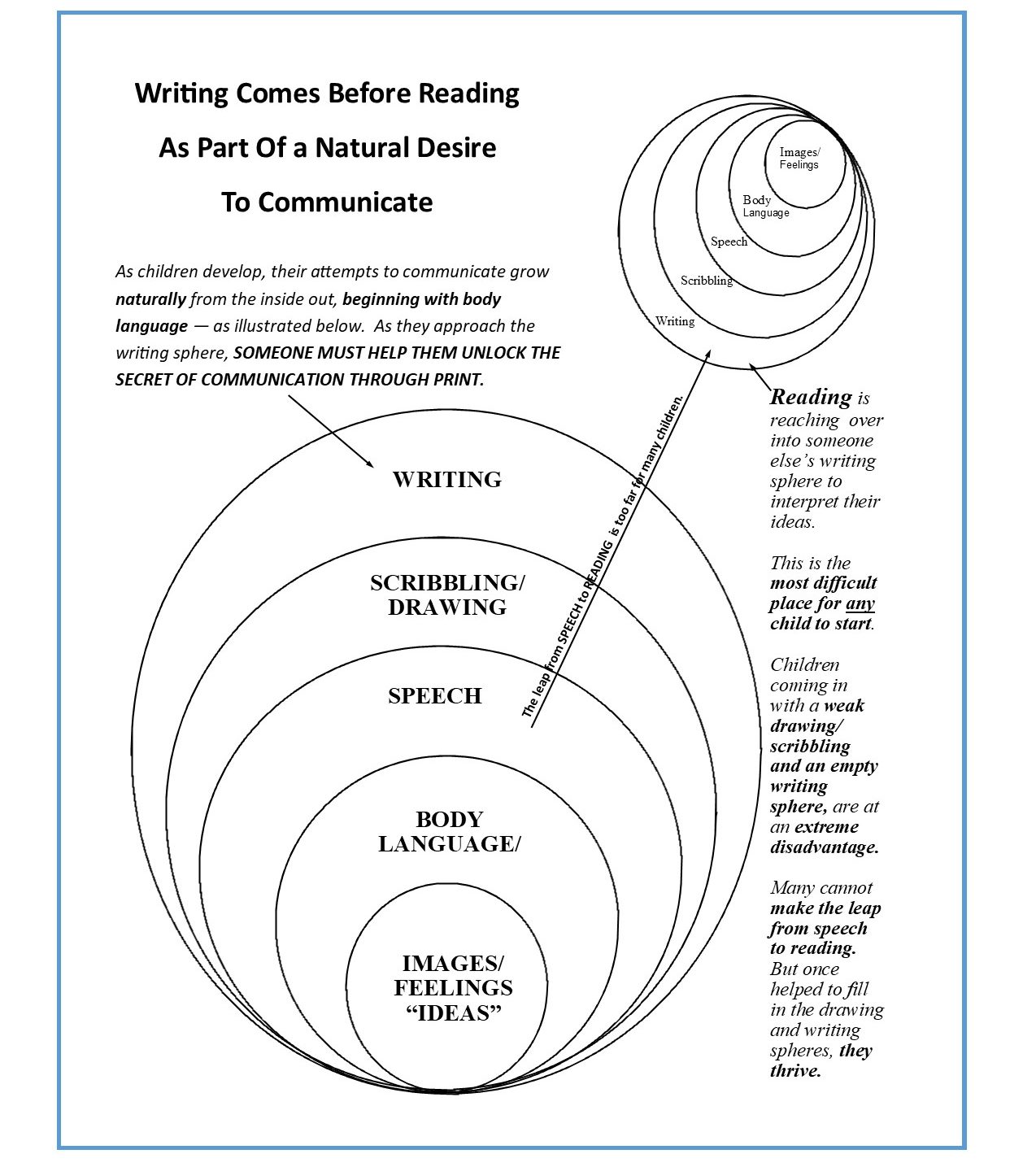

As the child grows, they continue to strive to communicate what’s at their center. So once they can speak, their next challenge is to translate their speech into print.

If we combine this with the realization that they most readily copy what has strong meaning for them, we can devise practical strategies for an approach that’s “natural” for the child.

Doing that over the years, I have found that a child will progress through 5 increasingly complex stages toward reading books.

So let’s look next at the child’s natural path.

5 Stages in A child’s natural Path toward reading

As Figure 1 illustrates, from birth forward, the child is intent on communicating what’s at their center.

As an infant, they convey their feelings through crying, and other forms of Body Language. Before long, they begin to develop Speech.

As an infant, they convey their feelings through crying, and other forms of Body Language. Before long, they begin to develop Speech.

Virtually all children make it this far.

If in a print-rich environment, they will begin to Scribble. And it’s here that we need to intervene. And here we use a similar technique we used with speech, to model how their own speech is translated into print. That is, we model and wait patiently while they figure out how to copy what they see us doing.

With this, the child continues ultimately working through the following 5 stages:

1. Crying/Body language –>

2. Speech –>

3. Scribbling/Drawing –>

4. Writing —>

5. Reading Books

The child proceeds along this path propelled by their desire to communicate what’s on their mind. So the last stage for the child is Reading Books1 written by someone else.

This, as professionally created books represent what’s on someone else’s mind — or perhaps what an author thinks might be on a child’s mind.

It’s important to note that distinction: The child’s natural path toward reading ends with reading books others have written. It does not begin there.

What if a child is asked to skip writing?

Deciding2 to move a child from Speech directly into Reading Books, interrupts their natural process, making any child’s progress more difficult. Here’s how it can affect children from different home/preschool environments:

A. Child from a print-rich environment: These children have probably already reached the Scribbling/Drawing stage. But most have not yet moved into Writing — so here’s how the challenge looks for them:

1.Crying/body language –> 2.Speech –> 3.Scribbling/Drawing –> 4.Writing —> 5. Reading Books

When faced with a reading program that skips writing — one which begins with basal readers or by focusing on phonics, then phonics books — some may struggle a bit, perhaps a great deal. Yet it’s likely they will ultimately bridge the gap.

B. Child NOT from a print-rich environment: These children have stopped at Speech. So by skipping Scribbling/Drawing and Writing, the challenge for them looks something like this:

1.Crying/body language –> 2.Speech –> 3.Scribbling/Drawing –> 4.Writing —> 5. Reading Books

Too many of these children struggle, even completely fail to make the leap from speech to reading books. This negatively affects them in school and far beyond. And it is completely unnecessary.

A child who has not yet gone beyond Speech need not be at such a strong disadvantage. For if we show them how their own words look in print, they quickly come to realize print is “talk written down” and move steadily forward.

All children can be successful, as long as they have similar modeling from us. Some will just need a little more time. So we provide an individualized approach.

Key Words and The Steps Mirror the child’s natural process of learning to Talk

We don’t approach reading/writing in exactly the same way we help a child to speak. We are actually more intentional about it. But we do use a very similar process.

We model and wait patiently. The child absorbs and ultimately copies what they see us doing.

We use Key Words to do this, for these are the captions for a child’s “mind picture” about something with strong meaning for them.

To model, we emphasize the skills that go into writing their words. We point out the letters we use to make the sounds needed. And we show them how the letters are formed by having the child trace over them after we’ve written their Key Word.

Modeling in this way allows the child to experience the entire act of communicating through print — for we don’t pull the separate skills apart and teach them separately. They are always integrated into the act of communication. This again, mirrors how we help the child learn to speak.

Finally, to be certain the child will develop the skills needed to write and read independently, we use The Steps. These are a series of follow-up activities to Key Words. They allow the child to go — at their own pace — through increasingly complex stages, just as they did with speech. Only this time, we direct their development — but still leaving the pace of skill development to the child.

For how to do all this, see Key Words & The Steps.

__________

1. The term “Reading Books” refers to the “cold” reading of professionally published books. But in fact, the child as been “reading” long before this. First, we have been reading nursery rhymes and children’s books to them early and often — with them sitting beside us, perhaps repeating some of what we read, singing with us, and helping us turn the pages. But on their own, they have also learned to read people’s expressions, body language and intonation. They have been reading/recognizing labels and the writing on their cereal box, and so forth. Read more about the complexity of reading.

2. For more about this decision, see the subheading, First Consider: Are We Teaching Reading Or Are We Helping the Child Learn To Read? on the page, Key Words & The Steps.

3. Read how once a child is writing their own thoughts, we move them into professionally published books.

4. This is my adaptation of Key Vocabulary, developed by Sylvia Ashton-Warner. A detailed practical description on the page Key Words & The Steps. “The Steps” are follow-up activities I devised for Key Words. The website, KidsWriteToRead.com also includes more about phonics, classroom management, some math, and virtually all other aspects of a natural approach.