I’ve noticed that when considering curriculum for young children, some adults have a tendency to look back to their own high school or college years. They think of the content their classes covered: History, Science, Math, English, and so forth. Then in extreme cases, they plan how to provide a scaled down version of such things as Ancient History, Scientific Discoveries, etc.

But a young child is not ready to deal with content unrelated to their own life, and it’s not the right time in their development for them to focus on acquiring new content.

So on this page, we consider curriculum that’s appropriate for a young child.

What is curriculum — and what’s our long-term goal?

First, the ultimate goal of this approach is to equip the child with the skills and habits that create a life-long love of learning — and for them to be inclined and able, to help make things a little better in the world around them. So the curriculum described here is developed with this goal, and with children from preschool and up, in mind.

Curriculum is defined here as the content and activities a student is working on. It’s not something you buy and move a child through, but something you piece together from various sources. For it’s meant to be personalized, to match each child’s interests and their natural process of development. This page describes the critical features of a personalized curriculum and gives examples of how it can be carried out.

Content for a Personalized Curriculum

A personalized curriculum is based on content meaningful to the child — something they’re very interested in. So for the young child, this content comes from their daily life, i.e. the people, animals, holidays, and foods they love; things that fascinate them, such as TV characters, dinosaurs; and even perhaps things they fear. So they’re working with anything of strong interest to them.

A personalized curriculum is based on content meaningful to the child — something they’re very interested in. So for the young child, this content comes from their daily life, i.e. the people, animals, holidays, and foods they love; things that fascinate them, such as TV characters, dinosaurs; and even perhaps things they fear. So they’re working with anything of strong interest to them.

Why begin there? Because it’s easier to learn something new, when we tie it to something we already know. And we tend to remember things that come to us with a strong emotional charge.

So in this approach, we begin by showing the very young child how their own “talk” looks, written down. We use those words to model for them all the skills that go into writing their thoughts, on their own. Later, once they can read/write independently, we elaborate on their interests by involving them in units of study. Such units, by definition, always ends with a project through which the investigate something they’re interested in.

It’s not until a child is older and has acquired the literacy skills — reading, writing, investigating, analyzing and multi-media reporting — that they can deal effectively with content farther out from their own life. If we attempt to teach them things too far out from their own life, the best we can hope for is that the child acquires new vocabulary that sounds impressive. But it may be pretty much devoid of meaning to them, and what information they gain will likely soon be forgotten.

So if expanding content isn’t the focus in the early stages, what it the appropriate focus? For the answer to this, we look what a young child is capable of and already trying to do at this time in their life.

A Personalized Curriculum Focuses on Expanding Communication Skills

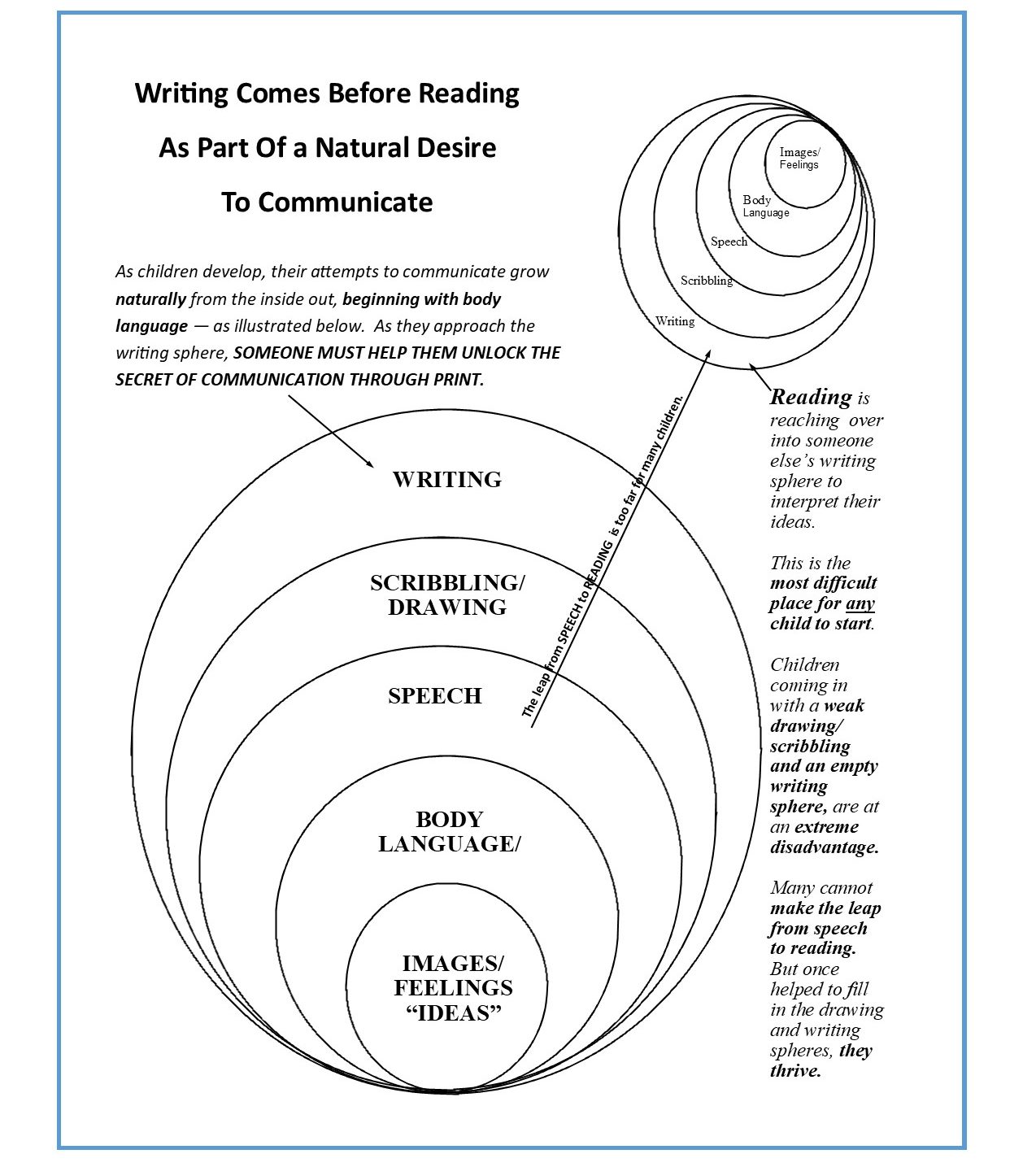

On the page, A Natural Approach To Learning, we looked at evidence that since birth, the child has been working on increasingly complex ways to communicate: The infant begins by using body language to tell us how they feel, and then they develop speech.

Their next challenge is to learn how to translate their own speech into print, and they’re ready for this earlier than many people realize.

Their next challenge is to learn how to translate their own speech into print, and they’re ready for this earlier than many people realize.

The image illustrates what neurological studies at Harvard conclude about brain development related to age. It appears the overlap of language and higher cognitive functions happens early.

The image illustrates what neurological studies at Harvard conclude about brain development related to age. It appears the overlap of language and higher cognitive functions happens early.

These findings have implications for parents and teachers. They appear to confirm Montessori’s theory that as a child’s brain develops, they go through what she called “sensitive periods” for learning certain skills.

It’s common knowledge that a preschool child more effortlessly learns a second language than when they’re older and have passed beyond their sensitive period for language. So now, these findings give credence to Montessori’s belief and that a child has more difficulty learning a particular skill once their sensitive period for it passes.

Findings also appear to confirm Montessori’s observation about readiness for writing. She believed that as a child reached a sensitive period for a particular skill, they would naturally be drawn to work with the materials she had provided to practice that skill. And she found the children gravitating toward writing materials at age 4 — just when studies show language is at its peak and the development of higher cognitive functions is on the rise.

So these findings seems to explain Montessori’s observations. And in working with preschoolers over the decades, I have found that it happens even earlier, if you begin by showing them how to play with their own “talk,” written down for them. They effortlessly “soak up” their own words in print — and remember them from the first day forward.

Translating Speech Into Print

Basic communication skills are: Speaking/listening and writing/reading.. A young child — say at three or at least by four — is already speaking well and ready to see how their own words look, written down. In fact, some children will try it out on their own, by scribbling on their drawings, claiming to write the name of the object they’ve drawn. For instance, they bring us a drawing and say something like, Look, I made our new kitty, as they point to a blob. And, Here’s where it says Fluffy, as they point to a scribble.

Whether they come to the idea that print is talk written down on their own or not depends on their environment. A child surrounded by print, has been read to often and seen adults writing notes, emails, etc., may figure it out for themselves. But if not, Key Words will help them unlock the secret of print. Following is how we use Key Words to help them do that:

A Key Word is one, two or sometimes three words that serve as the caption for the child’s “mind picture” of something they’re very interested in. As a child tells us what’s most on their mind at that time, and we respond to them in a way that elaborates on and expands their own vocabulary.

Then we help them settle on the best caption for what they’re thinking. The caption might be something like, puppy, ice cream, or Christmas tree lights. Then we write their Key Word on a card, and as as we write, we say the names and/or sounds of the letters we’re using. Then we have them do something with the word.

The first thing the child does with their “word card” is trace the letters with the index finger of their writing hand. Then a child who cannot yet draw will play with their word: Say they’ve asked for dog. The may show their dog the card and tell them that it says, dog. They may put it next to their dog’s bowl or in their bed. A child who can draw, makes a picture of their dog and glues a duplicate of the card under their picture.

With this, we’re beginning to help the child see how to translate their speech into print. But Key Words alone are not enough. To build writing stills, we gradually increase the complexity of what they do with their word card. For this, we have 6 follow-up activities leading to independent reading/writing. These are known as The Steps.

So these two strategies are how we gently support the child as they move toward writing fluently. And the writing skills they gain transfer to reading.

For more detail about how we develop both reading and writing using these strategies, see in Key Words & The Steps, and in Key Words With Preschoolers.

Higher level thinking skills come next

When a child is beginning to read and write with ease, we turn our attention to the higher level thinking skills of Investigation, analysis, and multi-media reporting. Here, we begin by showing them how to carry out simple “real life” projects. For example —

They may take a simple, three-choice survey of children in their primary-grade classroom, or their family, if learning at home: Which do you like best, bananas, apples, or strawberries? Then they illustrate the results in a 3-bar graph, and accompany that with a 3 sentence report: I asked what children liked best. Then I made a chart showing what they said. It was fun and I’m going to do colors next.

We increase the complexity of these projects to support their growth as they move farther into the Higher Cognitive Functions shown on the image from the Harvard studies. It’s with increasingly complex projects that they expand on content already somewhat familiar and of interest to them. For how to do this, see Projects — For All Ages.

With fully developed communication and higher level thinking skills, the older child is finally able to deal effectively with content and concepts farther out from their own life. Providing a child with a content-focused curriculum before they’re ready, they might learn the new vocabulary, but it’s virtually meaningless to them. And they will likely forget any information they “learned.”

You can easily design a fully personalized curriculum yourself

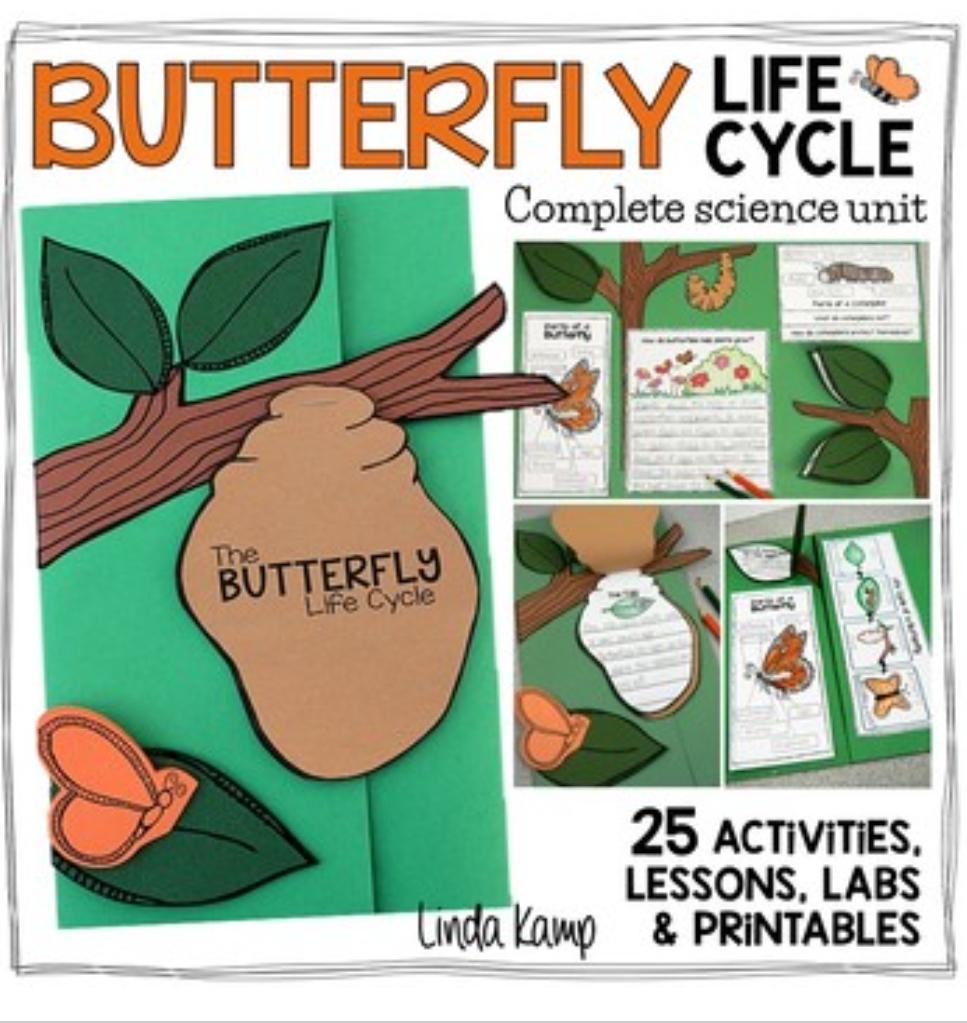

It may sound like a daunting task, but not if you do it just one step at a time — as you go. You don’t need to sit down and plan out the entire curriculum, in advance. You need to know what basic strategies you’ll use. If they need to develop their reading/writing skills (Key Words & the Steps), or whether your child is ready for projects. So you don’t need to do any more than start a young child with Key Words and slowly take them through The Steps. (Parents: this won’t be all you’re doing, but the rest of your curriculum is things you already know how to do, such as read to them and explain things as you going about your daily routine. See Learning At Home.) Or if working with an older child, you simply show them how to google a topic they’re interested in and guide them through a unit of study. See Projects — For All Ages, for how to design or where to buy units. I found the example shown here online, for $12.)

It may sound like a daunting task, but not if you do it just one step at a time — as you go. You don’t need to sit down and plan out the entire curriculum, in advance. You need to know what basic strategies you’ll use. If they need to develop their reading/writing skills (Key Words & the Steps), or whether your child is ready for projects. So you don’t need to do any more than start a young child with Key Words and slowly take them through The Steps. (Parents: this won’t be all you’re doing, but the rest of your curriculum is things you already know how to do, such as read to them and explain things as you going about your daily routine. See Learning At Home.) Or if working with an older child, you simply show them how to google a topic they’re interested in and guide them through a unit of study. See Projects — For All Ages, for how to design or where to buy units. I found the example shown here online, for $12.)

Content Finally Becomes the Focus

By the time a child can plan and carry out complex projects, they will have built a foundation of skills that will allow them to take on the serious study of content we associate with well-designed high school and university classes.

So it’s later, after a child has the process skills that curriculum can be more heavily weighted toward content. Once there, state and local documents can provide guidance or suggestions for content.

As always, we keep the child’s interest in mind, for our aim is to arm a child with all they need to establish a life-long habit and love of learning and the inclination to become a contributing member of our society.

What Makes This Curriculum Effective

Interest. Focusing on skill development does not mean the young child won’t be dealing with content at all. It’s just that the topics they explore will be related to something they’re truly interested in.

For interest is a strong motivator and a powerful magnet for skill development.

For interest is a strong motivator and a powerful magnet for skill development.

Content Is “Meaningful.” Recognizing the importance of interest, we look for signs of interest in topics that have meaning for them. So meaningful content is based on something they know from their daily life. They’ll have ideas and questions about to gardening, cooking, shopping, pets, other animals, holidays, and more. Plus, we all know how a child can become fascinated with such things as cartoon characters and dinosaurs.

Why begin with what they already know? Because we all learn best by attaching new skills and concepts to something we already know something about. That’s why professional publishers try to use “grade level” words to depict experiences they think a child will be interested in and understand. With this approach, we make certain this is so, by using the child’s own words. So early on, we use content not as an end in itself — but as a vehicle for skill development.

Skills Are Integrated. Instead of breaking the act of writing or reading apart and teaching the skills in isolation, we model for the child how their own “talk” is written down, using Key Words. As they watch us, they see and begin to absorb the skills involved in writing/reading. So all the skills are integrated into the process. For how this mirrors the way we help a child learn to talk, see How And Why A Natural Approach Works.

Skills Are Integrated. Instead of breaking the act of writing or reading apart and teaching the skills in isolation, we model for the child how their own “talk” is written down, using Key Words. As they watch us, they see and begin to absorb the skills involved in writing/reading. So all the skills are integrated into the process. For how this mirrors the way we help a child learn to talk, see How And Why A Natural Approach Works.

With the daily exposure to this modeling, the child effortlessly begins to absorb and practice the skills, in the context. This is instead of memorizing a list of sight words, the common letter/sound combinations, or spelling words. (It is not unusual for a child to get 100% on a spelling test, then misspell those same words in their writing.)

Learning is Active. We give the child something to do with their Key Word. As they leave us with their new word, the very young child will find a way to match it to things related to it, by for instance, putting the card with the dog’s name on it in the

Learning is Active. We give the child something to do with their Key Word. As they leave us with their new word, the very young child will find a way to match it to things related to it, by for instance, putting the card with the dog’s name on it in the  dog’s bed or beside their bowl. See Key Words With Preschoolers Or they’ll draw a picture about it. With this, they’re making a book which they’ll read to themselves and to others.

dog’s bed or beside their bowl. See Key Words With Preschoolers Or they’ll draw a picture about it. With this, they’re making a book which they’ll read to themselves and to others.

Where Curriculum Planning Goes Wrong

Not considering the following question is where adults go wrong and why too many children are introduced to reading in ways that make it more difficult for them than it need be:

Am I teaching reading and writing — or– helping a child learn to read/write?

In the example of planning to teach a young child Ancient History, — the adult sees their job as “teaching a subject.” It might be Math, Science, Reading, etc.. So the first thing they do, is break the subject apart, and if working with a young child — slowly relate it to them is small bites. When it comes to reading, the tendency is the same: break the act of reading apart and teach the skills separately. Or — expose the child to reading and help them figure it out.

I suggest, instead, that the challenge is to help a child learn math, science — or in this case — read, write and use higher level thinking skills. To consider what a huge difference this makes when it comes to reading/writing — and why so many children cannot overcome the challenge of traditional programs, see Are You Teaching Reading or Helping A Child Learn to Read and Write?

Helping The Child Learn to Read, Using a “Natural” Approach. Here, the first thing to do is analyze how a child learns — naturally. And since nature has given virtually all children the ability to learn to speak — without professionally designed lessons — a good place to look for guidance in designing a natural approach is how we help a child manage that.

Please note, I’m not saying we’re looking at how a child learns to read — that remains a mysterious, and much studied process. I’m saying we should look at what we do to help them — and for that we can see for ourselves. For discussion of the “reading wars” and emphasis nowadays on the “science” of phonics-first, see

Analyzing that process, here’s basically what we find: As they go about their daily routines, parents/caregivers repeatedly speak words with strong meaning for the young child. Combining those spoken words with some “real life” activity/purpose, they are modeling speech.

While they may speak in complete sentences, they have a natural tendency to emphasize, through volume and intonation, the main word that describes the associated action or object. Studies in various countries show this appears to be a natural tendency on the part of the adult. They don’t expect a response at first, just allow the child plenty of time to make the connection between the word(s) and the action or object it represents.

Hearing and watching this, the child gradually absorbs the information and makes all the physical connections that go into speaking those words. That is, caregivers make no attempt to break the words down into their component sounds and then present lessons to demonstrate how the child must coordinate the tongue, lips, throat, and breath to make those sounds. They can see the child has come with innate techniques for doing this, on their own.

So all that parents/caregivers appear to do is speak, with a slight emphasis, words they can see would be of special interest to the infant — milk, mommy, daddy, cookie, etc. — in conjunction with the corresponding action or object. The child’s brain does the rest.

At first, all we can see of the child’s effort is some spontaneous babbling, apparently serving as trials and practice for creating the sounds they’re hearing. Then finally one day, they delight us by speaking their first word. And so on it goes, as they continue to watch and listen, then practice and gradually expand –building vocabulary, incorporating intonation, and developing sentence structure — all quite spontaneously.

__________

*This discussion of teaching skills in isolation brings up the question of worksheets: The problem with them comes when the child works on them instead of using the skill involved as part of the complete process of writing their thoughts. But they can be helpful to hone a skill a child is already using, especially in the case of letter formation. and word families. So worksheets might be a choice activity, separate from the regular Key Words writing session. But no child should be required to use them as the sole teaching device, as a “make work” activity — or as a test. For a test is always what a child can actually do when attempting to communicate through print.