This page focuses on how to introduce Key Words — to one child, or to a small group of children in a classroom. It then provides detailed directions for giving words at each of The Steps. The page ends with an overview of all 6 Steps, along with some tips on letter formation and the use of pens/pencils.

Routines, and Procedures

As visitors to my classroom watched the children work with Key Words, they often asked how the children came to be so intent on what they were doing.

They remarked that not only were the children very interested in what they had chosen to dictate or write about, but that they were behaving in an unusually orderly fashion. So I’m including here how to establish the routines and procedures that prompt children to operate that way.

As you’ll see, introductions to important materials and procedures are made through what Montessori referred to as a Silent Demonstration. These are distinguished by slow, exaggerated movements, carried out in complete silence. Seeing a teacher behave in this way fascinates the children, prompting them to carefully copy the procedures being modeled.

I can’t emphasize this enough: Silent Demonstrations are invaluable. For they contribute to the development of a smooth-running, active classroom, which in turn, frees up the teacher to give undivided attention to individuals.

There’s more to creating such an atmosphere than I’m describing here, of course. So I’ve expanded on that topic later in this website, in 3 pages: 1. Classrooms: Control,Work Cycles and More, 2. Getting Started, and 3. Supportive Environment.

Following is a detailed example of how the introduction to Key Words might go. Please note that I’m not saying you must go through the exact procedure outlined here. But you do need to think through carefully and practice ahead of time the exact procedure you want children to follow. For once a routine is demonstrated and the children have copied/internalized it, you may find it difficult to change.

Introducing Key Words

Getting Started: An Example of How To Introduce Key Words To A Group

1) Bring no more than four children at a time to your table. Have large writing books prepared with colored covers — with several copies of each color. (See the subheading, “Prepare Materials for Key Words,” on the page, Getting Started.)

Invite each child to choose the color they want and write their name on the front of their book, as they watch. Also give each child a metal word ring and a word card with a hole already punched on the left end (as shown in the image below).

Write each child’s name on their card and have them practice opening the ring, placing their name card on it, and closing it again. Have them place their book and word ring in front of them, fold their hands on top, and watch as you begin Key Words with the first child.

2) Begin your introduction to Key Words with the child you expect will respond most freely to your invitation to talk. Go through the procedure outlined for Step 1. (These are described below, under “DETAILED PROCEDURES…” on this page.)

3) Once the child has their word card and duplicate, get up from the table, taking all the children with you. Have the three children watching leave their books and rings behind. (You are about to demonstrate the entire follow-up procedure, and you will do this only one time, so be sure everyone is watching and has ample time to practice.)

4) Stop first where you have a paper punch tied with yarn or string someplace nearby. Explain that they will come here to punch a hole in their word card every day, and show them how to use the punch. Let each child practice on scrap, card stock paper. Then make a mark on the first child’s word card where the hole should be, and have that child make the hole.

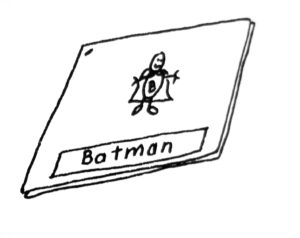

5) Go on to where you have prepared a Gluing Station. Tell them you are going to show them how to glue, that you will not talk, and that they must be completely quiet, too, and watch carefully. Wait until everyone is quiet and watching. Then use a Silent Demonstration to show them how to apply glue to the duplicate of the word you have already given the first child. Show them where it will be placed the first page in that child’s writing book.

Focus especially on placing the duplicate upside down on a separate piece of paper provided for that purpose before applying glue. Then show how it will be placed it on the bottom of the page in the writing book, so it will appear under their picture. (But do not place it down onto the page.)

Then — speaking again now — while the others watch, let that child add more glue to their duplicate and place it on the page in their book. Have extra scraps of paper handy so all of the children can practice gluing and pretending to place it on the bottom of a page — without placing it down. (Pretending — just to save on paper.)

6) Walk everyone over to show them where they are to put their books after they have been checked. While there, explain to the first chil d, as the others listen, that they are to make a picture about their word and bring it to you when finished — to be “checked” and receive their pin* to signal they have finished their work.

(See more about checking work at the bottom of this page.* This topic is also discussed in Establishing Teacher and Student Work Cycles.)

7) Let the first child choose where they want to work and leave them there, reminding them to show you their drawing, once it’s finished. Return to your table with the other three.

8) Go through the procedure for Step 1 with the next child. Differences from here on will be twofold: The rest of the children will go alone to carry out the procedure they already all have practiced. And you will make a mark showing where the hole is to be punched on each child’s word card, before they leave your table. (They usually only need this the first time they do it.)

Once the children have watched another child get their word, you might want to invite them to start their drawing, rather than just sit and watch — if, that is, they already know what word they will be asking you to write for them.

Detailed procedures for giving key words at each step

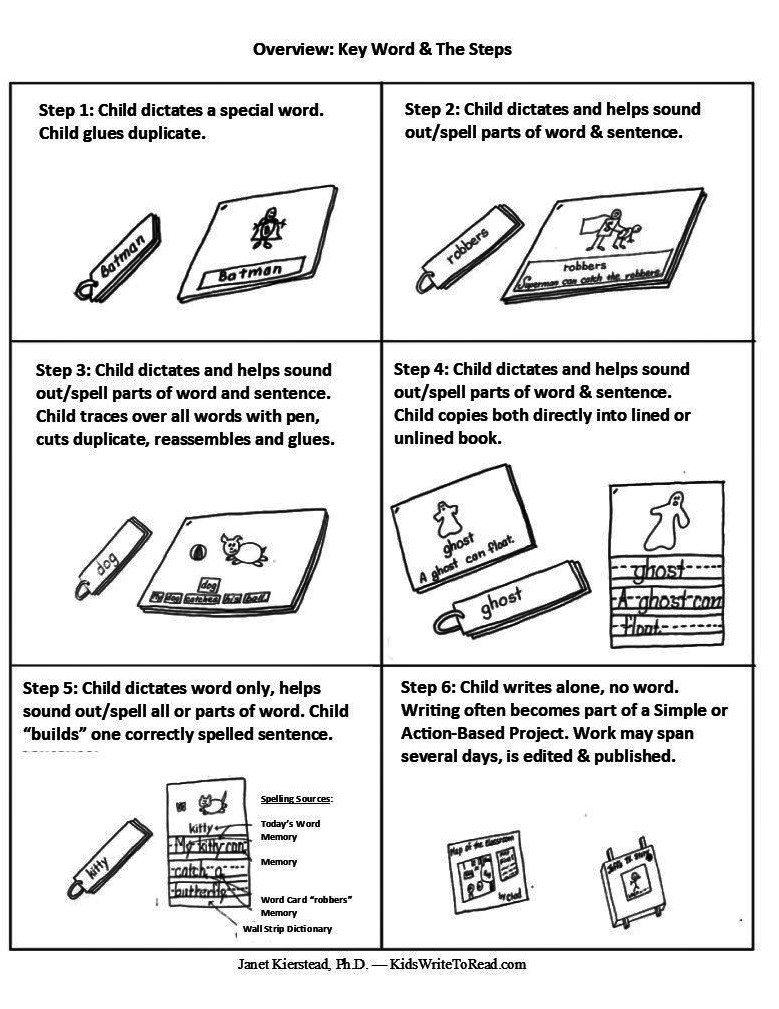

No matter how advanced the children are, it’s best for all to begin with Step 1. For at this point, they are just learning the routine.

No matter how advanced the children are, it’s best for all to begin with Step 1. For at this point, they are just learning the routine.

But they will all soon move on to Step 2, and those more advanced will move quickly on to the later Steps. Since they will all be going at their own pace, it will take some weeks, others months or even years to reach Step 6.

As they move through The Steps, a card with the appropriate directions for that Step is placed on each child’s Word Ring for helpers to follow. (Links to printable PDF versions of these directions appear on the following page, For Aides & Volunteers…)

take words off the ring a child does not immediately recognize

Key Words connect to the inner child. They allow skills to “stick,” because they have a strong connection to something with meaning for the child. And they give a child confidence with print.

It’s far better to have a small connection of powerful words, that give a child confidence, than a larger collection the child is not certain of.

So always take off any words a child doesn’t immediately recognize. Say something like, “That wasn’t a good word — let’s find a better one today. ” Never give hints or help them sound out a word.

If a child is forgetting words, take a little extra time. Talk long enough to settle on something they really care about, for which they have a strong “mind picture.”

So now, lets look in greater detail at exactly how to work with a child during the initial introduction (outlined above), when all children are at Step 1.

Step 1:

1) The child “reads” all the words on their Word Ring. (At the beginning of the introductory session, this would be their name.)

2) Ask some questions until you strike a chord: What’s your best toy, special person? What’s something really scary? Do you have a pet — and if so, what’s it’s name, what does it like to do?

Wait for something heart-felt to emerge.

3) Talk about what the child has settled on. Encourage them to describe it in some detail: what’s happened, what it looks like, why it’s important, etc. The girl in this example has seen the book, Bedtime for Batman, and tells some of the story.

4) Determine the word that best describes the child’s thinking. Here, she has talked about both Batman and bedtime. Listen carefully to hear whether you should write “Batman” or “bedtime” for her word.

4) Determine the word that best describes the child’s thinking. Here, she has talked about both Batman and bedtime. Listen carefully to hear whether you should write “Batman” or “bedtime” for her word.

(It’s best not to ask, Do you want Batman or bedtime? That may cause the child to focus on both words equally, which might interfere with their thinking — confusing them when they think back on this session tomorrow to remember the word. It’s better to say, What word should I write? That will tell you which “mind picture” and word they are already most focused on.)

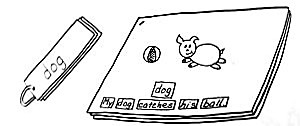

5) She has asked for Batman, so then say, “Now watch: I’m going to write Batman for you.” (Write on sturdy card stock, as shown below.)

6) Say the NAME of each letter as you write. (Most names include the sound, and many children already know the names through the Alphabet Song.) If the child’s eyes wander away, stop writing, and explain you can’t continue writing until they are watching.)

7) Have the child use the index finger of their writing hand to trace over the letters. If they go a different direction your letter formation program requires, stop them, demonstrate with your finger the direction they are to learn to go. Then them try it again. Do NOT try to guide their hand. (See charts at the bottom of this page for examples of letter formation.)

8) Make a duplicate of the word on newsprint, for the child to glue into their book.

8) Send the child off to the paper punch and Gluing Station — and later to make a picture about Batman.

9) Remind the child that they are to bring their finished work back for you to see. (After they return and you check their work, send them off to find an activity from the the Supportive Environment you have established.)

At Step 1, then, the child is learning —

-

that written words are a means of communication,

- correct letter formation,

-

use of the glue, pens, paper punch,

-

responsibility for completing work and having it checked by the teacher,

-

finding another acceptable activity from the few portions of the Supportive Environment you already have in place (you cannot have everything done at once),

-

responsibility for not disturbing others, and

-

helping to straighten and clean up the room at the signal for the end of the work period.

Moving Through the Remaining Steps

Once the children are familiar with the routines, which usually takes 2 or 3 days — most are ready to go to Step 2, adding a sentence.

The teacher is always the one who decides when they are ready to move on and spends at least two days making sure they know what to do at the next Step. On the following days, they are assigned to an aide, parent or cross-age tutor. As time goes on, the teacher monitors their progress by calling them to the teacher’s table frequently.

Each step is just slightly more complex than the one before, and the teacher makes certain the child has mastered the requisite skills before moving them on. See indicators of readiness before moving the child on to the next Step.

Special page for working with preschoolers

The examples given here were developed for primary grades. For younger children, see Key Words With Preschoolers.

Step 2:

1) Have the child read all the words on their ring, and take off any they don’t immediately recognize. (Do not give hints or help them “sound it out.”)

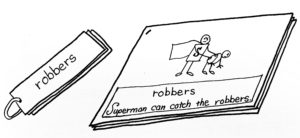

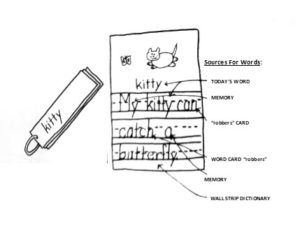

2) Talk. This child may have said, for example, I want “robbers” today, ’cause my dad showed me a special comic book he had when he was a little boy and it had robbers and Superman in it, and I really liked it. He’s really strong and so he can catch robbers. Then after that, we saw on the news about robbers, and my dad said there really are real robbers in the world…. In this example, the child has asked for robbers for their word (not Superman).

2) While writing the word robbers for the child, point out the spelling for ONLY ONE of the sounds that will be needed. More than one sound a day can be confusing. (For details about phonics cartoons and activities, see, What about Phonics?

Follow this procedure to show the child a sound they don’t already know. In this case, it’s the rrrr sound:

- Remind the child of the cartoon or picture for rrrr in the phonics materials you’re using. In this example, a motorcycle is revving up, showing the letter “r” coming out of the exhaust.

- Before you send them to look for the letter that’s on the cartoon, tell them that when they return they will need to be able to show you the letter they find by making it with their finger on the table. Have the child make the rrrr sound again before they leave you to find what letter is on the cartoon,

- When the child returns, have them form the letter on the table, with index finger of their writing hand.

- If they have forgotten it while walking back, don’t tell them — send them to look again. (Having to keep the sound and letter in mind, while going back and forth — then also having to trace it on the table — they usually remember it from then on.)

- Once they have correctly formed the letter on the table, write it for them on their word card.

3) The child traces, with their finger, over all the letters in the word. (See below for discussion of using pencils.***)

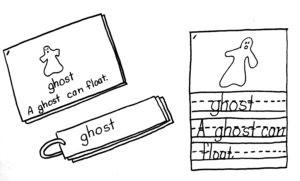

4) Help the child trim down what they’ve said, to make one sentence easy enough to remember and”read” back. This might be, Superman can catch the robbers.

The child watches as you write, and the two of you read the sentence aloud a couple of times. Touch each word as you both read. The child need only remember the word on the Word Ring, to keep it. They are not expected to accurately remember the sentence.

After a child has been at Step 2 for awhile, though, try asking them to point to the words as you both read. Once they are able to do that accurately and can point to the correct word — as you ask for it out of order — they can move to Step 3. See Indicators of Readiness To Move To Next Step.

5) You make a duplicate, the child glues it in, makes a picture, and shows it to you when finished.

5) You make a duplicate, the child glues it in, makes a picture, and shows it to you when finished.

At Step 2, then, the child is learning —

- the spelling for simple sounds (usually just consonants),

- that clumps of sounds are written as separate words, with a space between them (start by putting your finger after each word before you begin the next),

- the meaning of “sentence,”

- that sentences begin with a capital letter and end with a period or question mark, and

- how to choose a few simple punctuation marks: .,? (By listening to your voice as you read it back, making a sound for the punctuation, i.e., a click for a comma, a huh? for a question mark.)

Step 3:

Same procedure as in Step 2, but this time while the adult/tutor writes, the child helps supply the letters they know and refers to the phonics materials you’re using to discover and trace on the table the letter that makes ONE more new sound.

This time the duplicate is written by the adult on a narrow strip of paper and the child cuts it up. Each word falls on the table, the child scrambles them up and reassembles them. The adult/tutor helps the child “read” the sentence aloud, perhaps scrambles it again and has the child reassemble it. Each time they read/say the sentence again together.

This time the duplicate is written by the adult on a narrow strip of paper and the child cuts it up. Each word falls on the table, the child scrambles them up and reassembles them. The adult/tutor helps the child “read” the sentence aloud, perhaps scrambles it again and has the child reassemble it. Each time they read/say the sentence again together.

The child leaves the table, glues the words to recreate the sentence and completes their work, as before. I would keep the child at this Step a little longer than necessary, as long as they are not bored with it or impatient to move on. For reassembling the sentence a few times each day expands their base of sight words they can recognize and will later spell from memory.

A preschooler who still needs to learn to use a pencil (and may need help with scissors), also benefits from extra time at this step. For it allows more time for their motor skills to develop.

At Step 3, then, the child is learning —

- more complex spelling for sounds (the remaining consonants, some short vowels, and perhaps a few digraphs, depending on what the child has already learned during the previous Step),

- use of the sound-symbol relationship and configuration of the words as clues for identifying words,

- the spellings for function words, and

- use of scissors.

Step 4:

Same procedure as before, except that the child begins to copy the duplicate: At the Beginning Step 4, the child traces over with a pen what the adult has written with a pencil. At Advanced Step 4, the child copies the word and sentence directly into their writing book — either on lined or unlined paper, depending on their motor skills.

At Step 4, then, the child is learning —

- more complex spelling for sounds (remaining short vowels and digraphs, and perhaps long vowels by now, depending on what they have already learned),

- to form letters independently, and

- use of lined paper (not always, but perhaps, depending on motor skills).

Step 5:

Same procedure as before, except that the adult writes only the word and shows the child how to “build” a sentence from the supporting materials on the  classroom walls: charts of any songs or poems the class has learned; charts of Frequently Used and Service Words; a class “Wall Strip Dictionary,”which is within easy reach and used for recording words needed. More about these “living” Wall Strip Dictionaries is in Incorporating Phonics.

classroom walls: charts of any songs or poems the class has learned; charts of Frequently Used and Service Words; a class “Wall Strip Dictionary,”which is within easy reach and used for recording words needed. More about these “living” Wall Strip Dictionaries is in Incorporating Phonics.

At Step 5, then, the child is learning —

- more complex spelling for sounds (whatever spellings remain unfamiliar by now),

- how to spell words by “sounding them out,”

- how to locate spelling for words needed on the child’s own Word Ring, songs, chants, child-dictated “Today’s News” charts, etc., and most importantly,

- how to use the class Wall Strip Dictionary.

Step 6:

The child no longer gets a word. Instead they write long, complex stories and carry out projects related to math, science, or social studies. Children engage in two types of projects:

A Mini-Project: This is basically a report of something the child has learned through reading, conducting  interviews and/or surveys.

interviews and/or surveys.

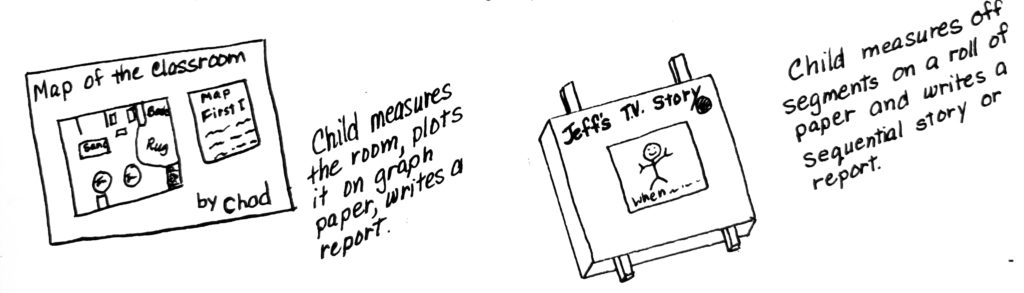

One example is making a map of the classroom to scale, writing about how they did it, and putting both on display. We used large, colored construction for a backing when displaying work. The child glued their writing on the right, which explained the procedure for measuring the classroom. The map was then glued on the left.

Another way of publishing a report — or just telling a story — is making a TV. Here you see the child has had someone cut a square hole in the front of a box.  Then on a long strip of paper, the child marks off sections the same size as the hole in the box. The paper is secured to two pieces of wood, so the child can twist the story to display the sections in sequence.

Then on a long strip of paper, the child marks off sections the same size as the hole in the box. The paper is secured to two pieces of wood, so the child can twist the story to display the sections in sequence.

Action-Based Project: This kind of project has a greater purpose in mind — to make a positive change, either doing it themselves or by influencing an authentic audience (i.e., someone or a group in a position to make the change). One example of this is extending the example above, by redrawing the map of the classroom, so that it shows how to make space for a new interest area — then presenting it to the teacher and the entire class to try to convince them, for instance, that they should rearrange one of the interest areas to allow for a puppet theater.

I developed the idea of Action-Based Projects in my work with older students for the California Dept. of Education, but these projects can also be simplified for younger children. For more ideas, see pp. 31 – 32 in my article, Yes, A Balanced Approach, But Let’s Get It Right!

overview of the 6 steps

checking work

With The Steps, a child is always operating at a level that’s relatively easy for them. You have a set of criteria to watch for when it’s too easy, but you never move them on if it’s going to be a struggle. Rather, they are just perfecting a skill you have made sure they are already capable of doing.

So when they bring you their work to check, it’s not going to have to be corrected. What you’re looking for is simply that they have actually finished their work. And it’s no good to go through a child’s work after school, only to discover didn’t finish their work.

So I established the requirement that a child bring me their work as soon as they finish it. It takes only a few seconds to glance at it and give your ok. At this point, you need something visible to signify that the work is complete.

I preferred to attach a clothespin to the child’s clothing, as it is a neutral, visual signal (but not a reward). And I collected the clothespins as the children went out to recess. Another teacher might initial or date the paper. Still others might have the children sign off on a “must do” chart.

It should be a fairly neutral signal, though, as research suggests extrinsic rewards can interfere with motivation when given for work that involves higher level thinking. This as contrasted with learning the multiplication tables, for instance. For since they are a rather low level memorization task, an extrinsic reward may actually be helpful. (Maher)

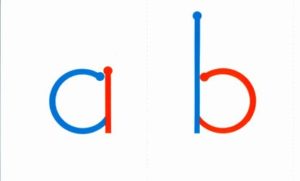

LETTER FORMATION

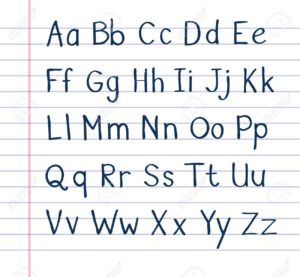

The charts below are for those of you who don’t have a penmanship program guiding letter formation. These are examples of how letters are commonly formed, in writing English.The first chart shows that you begin with the blue and attach the red. In each case start with the circle and move down.

introducing pencils/pens

As with all else, children differ in when they are able to use a pencil. The Steps follow-up activities don’t call for tracing with a pencil until the late 3rd or the 4th Step. Before that, it’s always done with the index finger of their writing hand.

Tracing with a pencil can also be delayed for as long as necessary by having the child key in on a computer or smaller device the words someone has written for them. In any case, their experience with print should not be held back by lack of motor control. Very young children will delight in seeing how their “talk” looks translated into print. And they will absorb the connections with ease, just as they did when learning to speak.

I would allow a child to hold a pencil or pen in any way they want until sometime around 3 1/2 to 4 years old. After that, I would try introducing them to the correct use of pencils, as the normal way of holding them will ultimately give them more comfort and flexibility. Here are some ideas for showing a child how to hold a pencil correctly:

Use an “Alligator Mouth”:

(Images from Jody A. video, Teach children How to Hold a Pencil Correctly Tutorial.)

materials to help when introducing pencils/pens

A short, triangle pencil is easier to hold correctly — or — perhaps try some pencil grips. These images were found from googling “devices for holding a pencil correctly.”

next —> For Aides and Volunteers: Detailed directions for giving Key Words

<— back Key Words and the steps