Projects develop higher-level thinking Skills

This page is still being developed, so it’s not yet fully edited. Please let me know if you find typos and glitches. This is a volunteer project, with no money for a copy editor. So I’ll much appreciate your helping me locate them.

Projects develop the higher-level thinking skills involved in investigation, analysis and reporting. With the world at the child’s fingertips through the internet, information is readily available. But they need someone to help them gain the skills necessary to access and make use of that richness.

Interest in Meaningful Content is Key

For the young child, projects must be based on something the child is interested in. Here, we refer to that as meaningful content.

So for example, with a young child — if they talk about a dog at home they love, we may show them how to conduct a simple survey to discover if others in the classroom have pets they love. Then we have them have them make a simple bar graph to report what they found. Following that, they write a three or four-sentence report telling what they did, what they’ve found, and perhaps what they’ll do next.

An older child, we may take that information farther, making a pictorial chart that shows the food and exercise various breeds of dogs need. Perhaps they make a pictorial chart showing that and write a little longer report. Another child may want to interview their grandparents on both sides and create a family tree.

Interviews, surveys, charts and graphs are valuable analysis and reporting skills. So we look at the skills we want them to develop — and see how something of interest to them can be used to develop them. (And we don’t have to make a list of all those skills ahead of time, for when we see what the topic is, the skills needed to gather and analyze information about that topic will become obvious to us.)

So projects are the way to prepare the child for life-long learning. But to be effective, a project must focus on a topic of true interest to the child. For interest is a strong magnet for gaining information and for developing skills. See more here about how interest matters.

Key Two types of projects

Learning to carry out “real-life” projects will allow them to investigate anything new they encounter, organize and make sense of what they find — and do something as a result of what they’ve learned. That may be simply reporting it in a way that makes sense to others. Or it may be taking some action suggested by what they’ve found. These higher-level thinking skills are valuable not only in classes later in school — but for their entire life.

This page gives you ideas for two types of projects — one “simple,” the other, “action-based.” In both cases, this page is intended to give you ideas— not recipes. You can adapt the projects described here for use by a child of any age. Just trim them down or expand on them, to meet the needs of your child.

The project examples I’m sharing here are based on the work I did in my own K-2 classroom and later, as a contract consultant for the California Dept of Education, conducting workshops with middle and high school teachers. I eventually also used them in classes I taught at Claremont Graduate University.

So I’m using here some of the illustrations I created for that work — because with school closings, I want to get these ideas out to you as soon as possible. So while these were written for classroom teachers, you can readily adapt them for use at home.

Developing A Unit of Study leading to a “real life” project

“Real Life” Projects are investigations into things a child is truly interested in — something they’re familiar with that they actually want to know more about. So they are a part of the child’s “real life.” They are the culmination of a unit of study. Here’s a very brief sketch of how a unit goes:

- Choose an area of study. It’s best if your child has already developed a fascination with something and you can help them delve farther into that. If not, then see if your state or local school district has curriculum guides that lay out topics by grade level. If not, think about your choices in terms of your child’s age and how far from their daily surroundings they are able to envision. So a young child may be more interested in things in the home and neighborhood — toys, pets, foods, or something they’ve seen on TV. An older child can focus farther out: homelessness, climate change, the current health crisis, fashion, music, etc. The main thing is that they’re honestly interested in it — because primarily it’s process skills you’ll be modeling for them — so that they can readily access and effectively treat any topic on their own for the rest of their life.

- Investigate the topic in a general way Read about it or show videos to the young child — or help older children to do that for themselves. (First, google How to teach a child to take notes and choose a method you’re comfortable with. I found an overview of 5 simple strategies here.)

- Begin a Project. Again, investigate as in #2. But now, with a little more information at hand, they can begin to dig deeper into the general topic. Here they may ask others what they think.

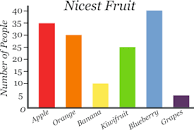

- If it’s something that lends itself to an opinion, show a young child how to design and carry out 3 or 4 choice opinion surveys. (Which do you like best, apples, oranges or pears? Or more difficult for the child: “What fruit do you think is the nicest?”)

- Show an older child how to study their topic more thoroughly– through the internet, books, journal articles, and newspapers. Show them how to plan for and conduct and phone interviews of informed family members, friends, or local

experts. (Most people are happy to be interviewed by a child.) These interviews can be closed, asking whether they agree with a few statements the child has posed. Or it can be open ended, as in “What do you think we should do about climate change?”

experts. (Most people are happy to be interviewed by a child.) These interviews can be closed, asking whether they agree with a few statements the child has posed. Or it can be open ended, as in “What do you think we should do about climate change?”

- Analyze and illustrate the results with graphs and charts. For the young child, this will be nothing more than adding up the various options they gave in

their survey. With this they can make a simple bar graph, with 3 or 4 bars. But if they’ve asked an open-ended question, “What kind of fruit do you like best?” Then they will have a more extensive graph. Click here for ideas for young children. For an older child, it might be even more complicated, if they’ve posed the question, “What do you think we should do — X, Y, or Z?”) In this case they will be creating a chart to show the results. See different types of charts for older students.

their survey. With this they can make a simple bar graph, with 3 or 4 bars. But if they’ve asked an open-ended question, “What kind of fruit do you like best?” Then they will have a more extensive graph. Click here for ideas for young children. For an older child, it might be even more complicated, if they’ve posed the question, “What do you think we should do — X, Y, or Z?”) In this case they will be creating a chart to show the results. See different types of charts for older students. - Develop a multi-media report.

- Write a Report. For a very young child, this would be dictating 3 sentences or so. Something like, I studied dogs like, Ruffy. Mom read me books and I

asked Grandpa, because he’s a vet. Dogs need lots of food and water, and they really like to go for walks. (Write it in exactly that child’s own words, so they can “read it” back.)For an older child, it’s the same, only they write it themselves, and in greater detail, following an outline you help them develop. For example, they would include the basics in their outline: What I studied and why, how I carried out the project, what I learned and what I think about it myself, and what I want to study next. This can be trimmed down for a younger child, and more detailed as the child’s writing skills improve.

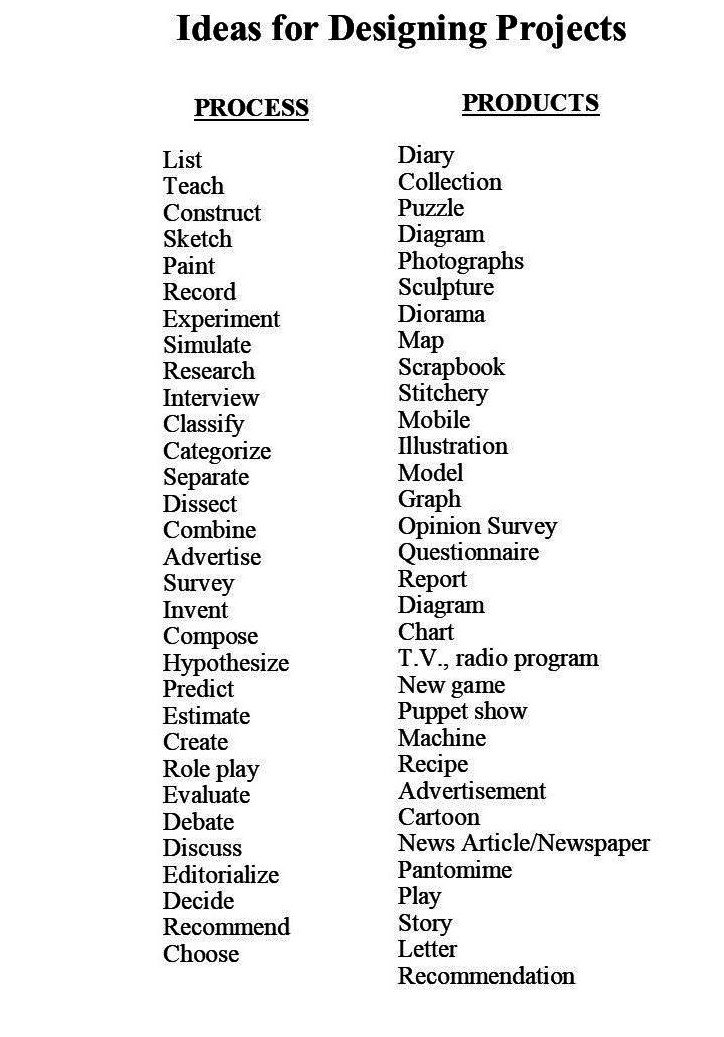

asked Grandpa, because he’s a vet. Dogs need lots of food and water, and they really like to go for walks. (Write it in exactly that child’s own words, so they can “read it” back.)For an older child, it’s the same, only they write it themselves, and in greater detail, following an outline you help them develop. For example, they would include the basics in their outline: What I studied and why, how I carried out the project, what I learned and what I think about it myself, and what I want to study next. This can be trimmed down for a younger child, and more detailed as the child’s writing skills improve. - Create a Product. This can be a drawing, a bar graph (to reflect the opinion survey), more complex graph (see “different kinds of graphs”), a timeline, or one of the many ideas listed below — or something else the child dreams up.

- Write a Report. For a very young child, this would be dictating 3 sentences or so. Something like, I studied dogs like, Ruffy. Mom read me books and I

Or — Buy Individual Units Of Study

You and an older child design a unit together. But you may want to purchase sets of detailed units that expands one of your child’s interests. For example, you might buy a unit on a butterfly’s life cycle, or some other topic your child is  interested in. (I found this by googling, unit of study on the life cycle of butterfly. Cost: $12.50)

interested in. (I found this by googling, unit of study on the life cycle of butterfly. Cost: $12.50)

Buying a few of these at first is helpful, for once you’ve carried out a few of them, you’ll have ideas for child-appropriate activities you can use with any topic your child is drawn to. More about designing units yourself in the page on the project page, linked above.

Rather than develop such units in this website, we’re focusing primarily on giving you the basic strategies for developing literacy skills — so that you can design a fully personalized curriculum yourself. (It’s like the give a man a fish, and he’ll eat for a day, teach him how to fish and he’ll eat for a life.)

So on other pages Key Words, The Steps, and Projects, which are the basic strategies for developing literacy skills: Reading/writing, and higher-level thinking skills. These basic strategies can be based on any topic, and as such, they are the heart of the personalized curriculum you’re designing. Once you learn how to use them — your curriculum is pretty much designed.

Real life projects can be “simple”or”action-based” projects

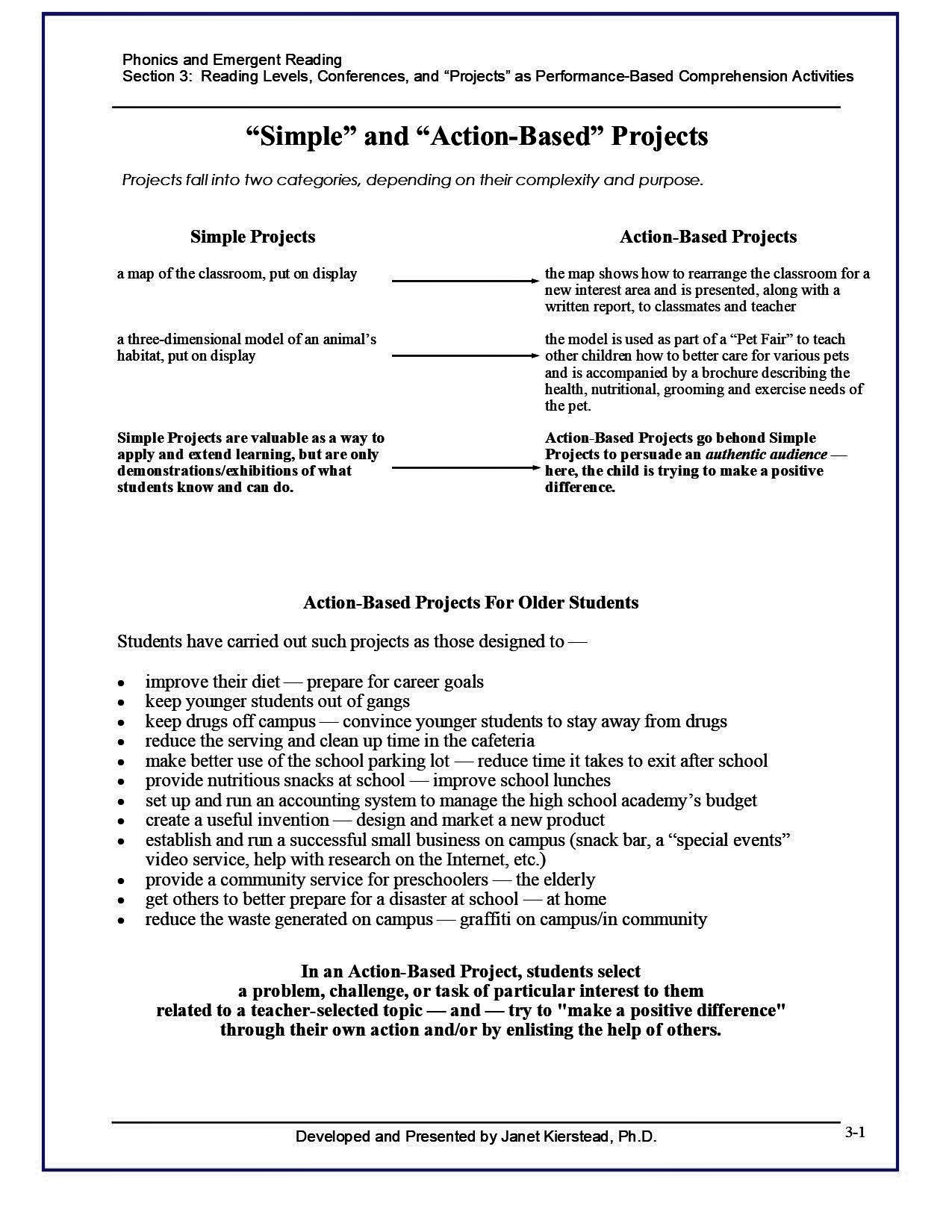

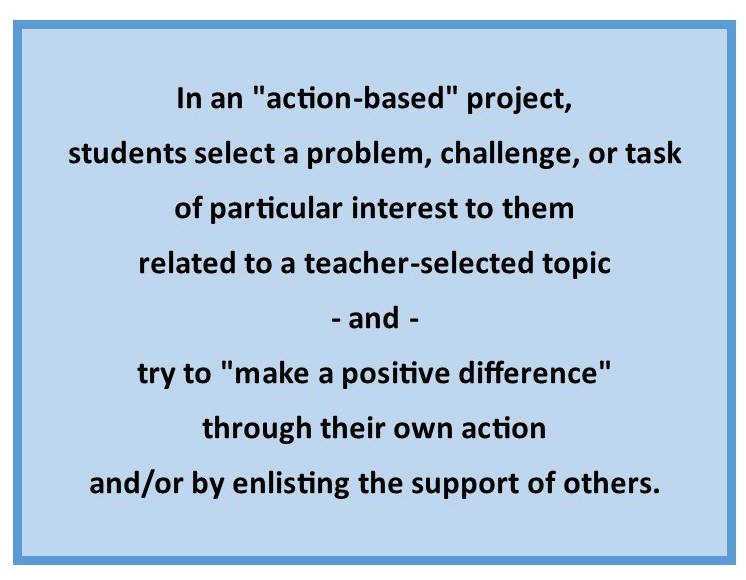

A Unit of Study can end with a project that’s a report, illustrated with product — or with an action-based project that goes beyond that, in an attempt to offer a service to or affect change in an authentic, “target” audience. Here’s the difference between a Simple and an Action-based project —

Example of an action based project aimed at making a change at home

A middle-school student created this project, but it could be scaled up or down, depending on age.

Simple examples for primary

One of the most popular projects for very young children is an Opinion Survey. They ask something like, Whats your favorite fruit: Apple Orange or Banana? They phone family and friends to gather opinions, then make a simple bar graph on half-inch graph paper and dictate or write the results. The child “publishes” their report and bar graph by gluing them side-by-side on large construction paper and placing it in a position of honor. (See Map of the Classroom, below.) They can also help address and mail copies to each person they interviewed.

One of the most popular projects for very young children is an Opinion Survey. They ask something like, Whats your favorite fruit: Apple Orange or Banana? They phone family and friends to gather opinions, then make a simple bar graph on half-inch graph paper and dictate or write the results. The child “publishes” their report and bar graph by gluing them side-by-side on large construction paper and placing it in a position of honor. (See Map of the Classroom, below.) They can also help address and mail copies to each person they interviewed.

The map of the classroom below can be a simple report, as shown here. Or it can be an “action-based” project as mentioned above — to convince the parent or teacher where a new interest area could be installed. Again, the child glues simple projects of this sort onto colored construction paper. This time, they may want to “publish” them by placing them into an ever-growing project binder. (These make great gifts for grandparents.)

The TV Story can be small — as with a matchbox, adding machine tape, and toothpicks. Or it can be large, using a cardboard box, a roll of drawing paper, and wooden dowels. Children frequently use them to create “documentaries” to report what they’ve learned. (Rolls of drawing paper are available on Amazon.)

The TV Story can be small — as with a matchbox, adding machine tape, and toothpicks. Or it can be large, using a cardboard box, a roll of drawing paper, and wooden dowels. Children frequently use them to create “documentaries” to report what they’ve learned. (Rolls of drawing paper are available on Amazon.)

Examples of Action-Based Projects for Older Students

Projects are particularly valuable for developing higher-level thinking skills and a sense of responsibility in older students. That is, responsibility in the way they carry out their project work itself, as well as responsibility for seeing themselves as part of an interdependent citizenry. To accomplish this, I developed the concept of Action-Based Projects. These projects were designed to encourage students to look for something they thought could be improved, and to carry out a project to make that improvement.

Then, as a contract consultant for the California Department of Education, I let teams of teachers throughout the state in designing curriculum to support student-designed Action Based Projects. In these seminars, teachers from dozens of middle schools and high schools in California came together to learn how to design these projects, then went back to their schools and taught this process to their students. When the teams met a few months later, they shared what their students had done.

I’ve compiled some of the Examples Of Action-Based Student Projects these teachers shared to the group. They’re in PDF format so you can print and discuss them with an older student — to spark their own ideas. Some might also be modified for use by younger children. You’ll notice some mention on the first page of “teacher-selected topics.” This was so that these project would be the culmination of a teacher-designed unit of study. Teachers selected their unit topics to align with the state and district guidelines.

I’ve compiled some of the Examples Of Action-Based Student Projects these teachers shared to the group. They’re in PDF format so you can print and discuss them with an older student — to spark their own ideas. Some might also be modified for use by younger children. You’ll notice some mention on the first page of “teacher-selected topics.” This was so that these project would be the culmination of a teacher-designed unit of study. Teachers selected their unit topics to align with the state and district guidelines.

For it’s at this point in their school career that students were expected to be studying certain things. But while the general topic was determined by someone else, the students were allowed to narrow that topic down into something that actually interested and concerned them. Teachers used the projects as the culmination of an entire semester, so there would be several general topics they’d studied during a full semester that they could choose from.

Managing Project Work

This section TBD but here’s a start: If you should find them getting bogged down, so that the project becomes a heavy chore, find some way to cut it short — without completely abandoning it. For you never ant them to lose interest in what they’re doing — and if they do, it usually means there’s something wrong with the work itself — not them. (Except in unusual personal circumstances, of course.) But at the same time, they need to get in the habit of finishing what they’ve set out to do.

join our facebook group to share ideas and stay in touch

For questions/comments and other strategies — and to share your own project examples, join the Facebook Group, Helping ALL Kids Write To Read.