This page is is still in construction. Please forgive glitches. This is an all volunteer effort, and there’s still much to edit.

Three Levels of Control

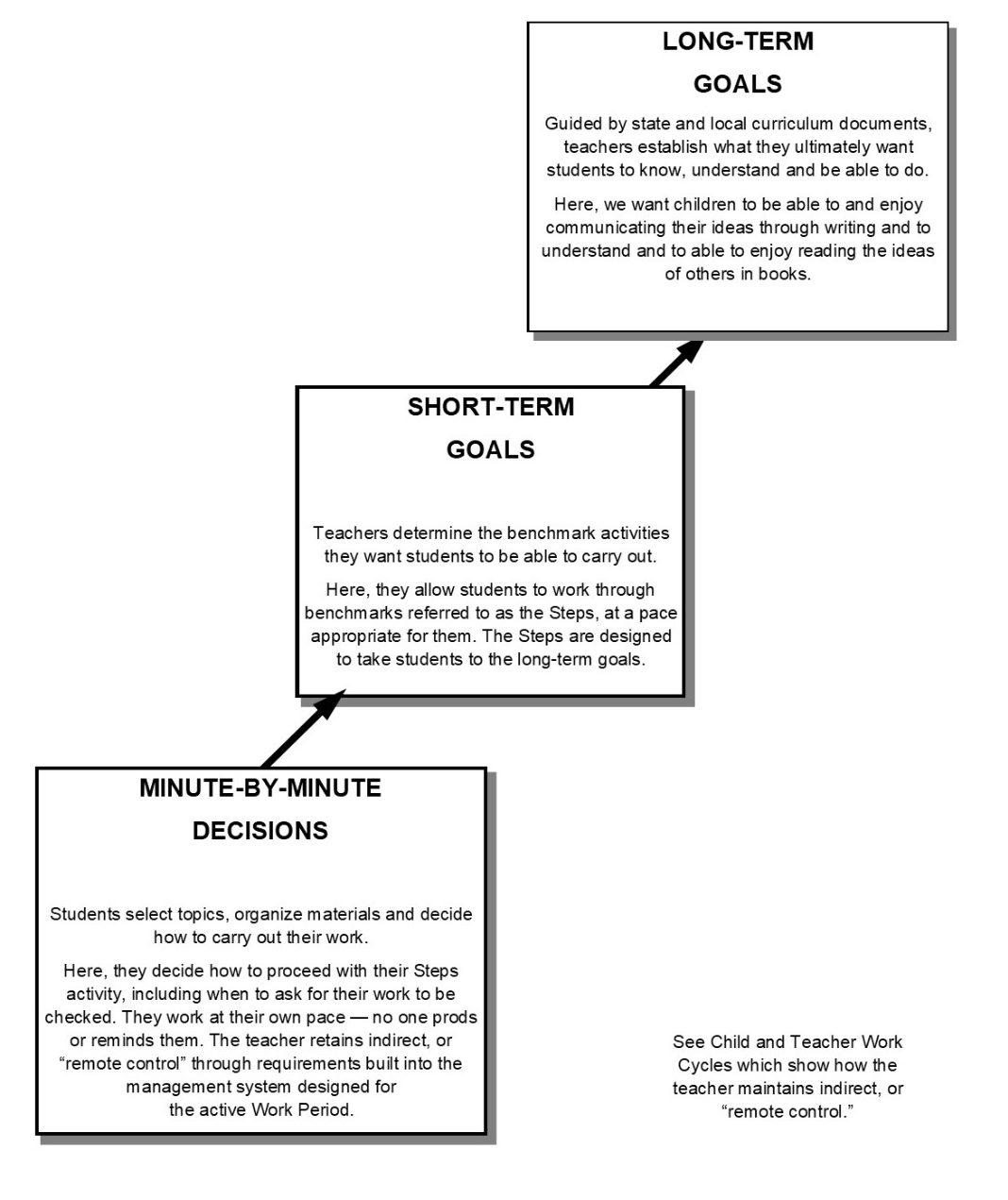

As the pendulum swings back and forth in education — between too little vs. too tight control — the arguments over this issue never seem to be clear or decisive. Too much interference, through tight control, can sharply decrease motivation. Too little control puts long-term educational goals in jeopardy. I’d like to see us settle this question by viewing it as a matter of having three levels of control, which allow for a sharing of control between governing bodies, teachers, and students, as follows:

Notice the parallel in families: Long Term Goals are established by laws and societal norms. Short Term Goals are established by parents/caregivers, and minute by minute decisions are best shared with children. If the balance of control is not effectively reached, problems result — ranging from over-control, resulting in abuse and possible rebellion — or — at the opposite end of the spectrum, wild, completely undisciplined children.

It’s What Teachers Should Accomplish — Not How They Should Accomplish It

Teaching truly is both a science and an art. Directing all teachers in a school or district to adopt the same particular set of practices or prescribed materials and activities — and demanding they provide”paperwork” as evidence of compliance, is too much control at that middle level. Such demands can dampen enthusiasm for teaching and interfere with creativity, sending good teachers out of the profession. While long-term goals should be clearly defined, teachers should be allowed to select and design materials and activities that make up their curriculum aimed toward those goals.

What’s Needed Is Ongoing Staff Development, Rather Than Strict Program Directives

Rather than being expected to carry out edicts from above, teachers should be supported by ongoing staff development that reminds them of “old,” but still valid, theories and research findings, and keeps them up to date on new findings and effective practices. There is information from research on such issues as motivation, interest, and intrinsic vs extrinsic rewards, task structures, for example, that can help teachers anticipate the positive and negative side effects of any given practice they are considering.

A good teacher develops and continues to perfect classroom practices over time — by being virtually continuously picking and choosing materials and activities that best suit their personality and the needs of their students. And there are very creative teachers with successful practices already in place in classrooms within or near most school districts. So visits to observe unusually effective classrooms are relatively easy to arrange and can give teachers ideas for approaches and strategies for designing their own effective practices.

In my study of Outstanding Effective Classrooms, I found such places by asking principals to identify classrooms where parents asked to have their children assigned, because that teacher’s students were known to love school, and to be especially motivated to read/write at home: I also asked other teachers to identify teachers in the area they particularly admired, for the same reasons. Of those identified, I chose to study those whose class scores on state tests were at or above those of classes with children from similar backgrounds. Within that group, I found some truly outstanding effective classrooms.

Bottom line is that I know such teachers are out there for all of us to learn from. So teachers should have staff development opportunities that provide information and exposure to them, then be given the freedom to create their own version of benchmark activities that make their classroom an interesting and vital place where students steadily grow. All of this should be aimed at helping students reach the long-term goals set by by state and local governing bodies. So again, it’s what teachers are to accomplish that should be clearly defined not how they should go about accomplishing it.

Students Should Also Know What They Are To Accomplish — Not Exactly How They Should Accomplish It

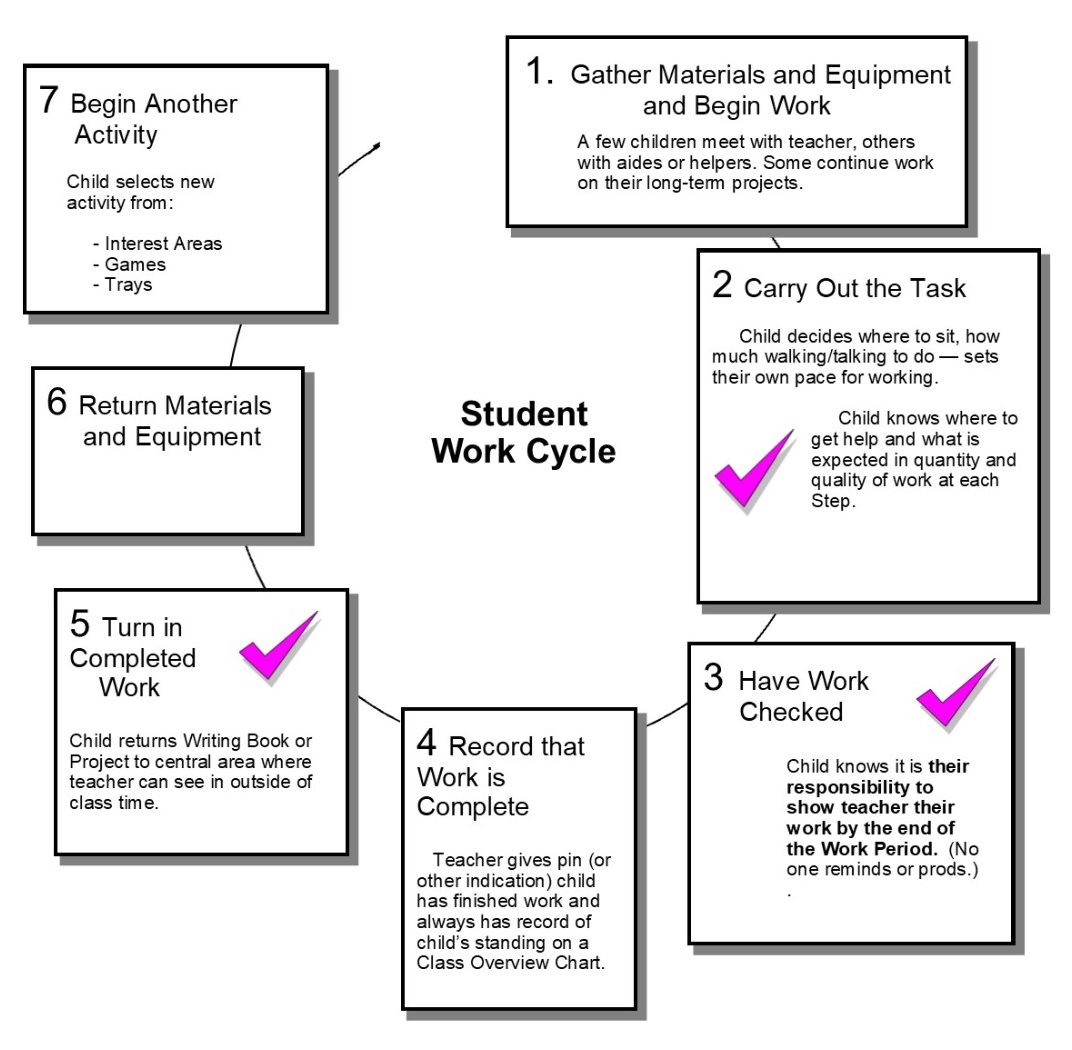

At the ground level, students should be allowed to take responsibility and control over the minute-by-minute decisions as they select and organize materials and decide how to carry out teacher-designed benchmark activities. For example, in my classroom, the children knew they must have their Steps activity completed and checked by the end of the work period. But how they went about it was up to them, as long as they were not disrupting someone else’s work in the process. That meant one child might dictate their word first, then start their picture — staying seated until it was complete, then immediately come to me to be checked. Another child might talk for awhile, then take time with their drawing before going to someone to ask for their word. They might stop along the way to watch what someone else was doing, or discuss something entirely different, ultimately finishing their work and having it checked much later than someone else. How they did it was up to them. My control was simply the requirement that they have their work checked by the end of the work period, that they follow the guidelines of the Student Work Cycle (below) and that they behave so as not to interfere with anyone else. The result was — as visitors often remarked — an atmosphere much like that of an adult workshop.

Setting Guidelines, Rules and Consequences

I ultimately thought of my classroom management strategies as a system of “remote control.” I had to set up the curriculum of benchmark activities and the supportive classroom environment of materials and activities in advance, and carefully convey to the children what I expected of them. Then I could allow them to make minute by minute decisions as they worked independently within the guidelines I had set.

I ultimately thought of my classroom management strategies as a system of “remote control.” I had to set up the curriculum of benchmark activities and the supportive classroom environment of materials and activities in advance, and carefully convey to the children what I expected of them. Then I could allow them to make minute by minute decisions as they worked independently within the guidelines I had set.

This meant I first had to establish that I was the one in charge. So I began this on the first day of school, by setting boundaries: With them sitting on the rug around me, I told them their work in our classroom was as important as when their parent’s went to work or worked at home — and that our one rule was, “We never disturb anyone else’s work.” We discussed that might be anything from yelling and running, to actually taking someone’s paper. Then I invited them to give examples of what “disturbing someone’s work might be,” as I recorded them on the chalk board. And they always enthusiastically envisioned inventive and colorful ones.

I explained that the consequence for disturbing someone’s work would be having to sit in a chair, facing the work area, and watch for awhile. I would have someone move a chair into position facing the tables, then as for a volunteer to sit on the chair, to show us what time-out would mean. (Later, when it did happen, I would show the child where the minute hand would be when 5 or 10 minutes was up, and tell them to let me know when the time was up. This, as I could get so involved with others, I might forget and leave them sitting there.

This “time-out” seldom happened, except for one unusually unruly boy who once actually stabbed someone in the hand with his pencil (among doing other slightly less violent things). For him, the chair eventually wasn’t enough, so I arranged to have him go for a time-out to the 5th grade classroom, where he had to sit in the back of the room, with no one allowed talk to him. Two times of that, and he came back saying that wasn’t any fun — and with that, he began to control himself somewhat better. (Although years later, his mother called to ask me for a referral to a psychologist, as his problems were increasing.)

Establishing Student and Teacher Work Cycles

Recall in Changed Student/Teacher Roles, I discussed the need to change how teachers spend their time. There, I offered the following formula:

Equal Concern = Equal Time Spent Regularly With Skill Groups

Equal Concern = Equal Consideration of Individual Need &

Time Spent As the Need Arises in a Child’s Work

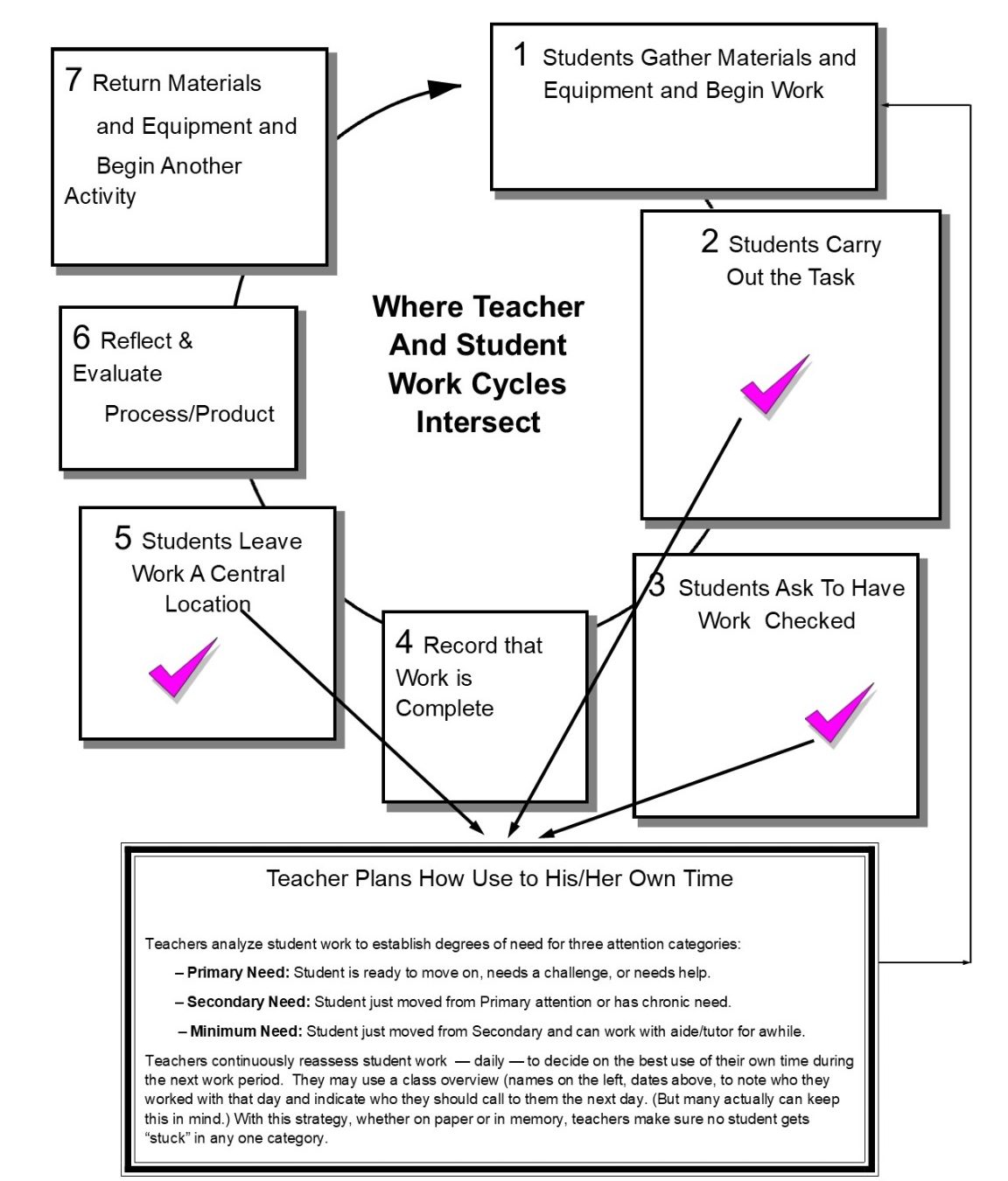

But how does a teacher establish a system where that can happen? To keep track of each child’s progress and thus decide how to use my own time, I developed the idea of “Student Work Cycles,” shown in the illustration below. I established the work cycle as I introduced the children to the process of working with Key Words. As a reminder, here’s a summary of the process as I outlined it earlier in Giving Key Words At Each Step:

I called 4 children at a time to my table. After collecting the first child’s word and duplicate, all of them went to the gluing station with the first child, where they practiced how to glue a duplicate. Then as we sent the first child off to draw a picture of their word in their book, I emphasized that as soon as that child was finished, they were to show it to me. I repeated that process until each child had their word and was off working. Then later, as each child finished, they would hunt me down wherever I was in the room. There, I would made some positive comment about what they had done, place a clothespin* somewhere on their shirt or blouse and remind where to place their book. I would also remind them they would need to hand their pin back to me when they went out for recess. Later, as the class went outside, I stood by the door and collected clothespins.

At the beginning of each new year, one of the new children might come up short, with no clothespin. So I explained that it would be okay for this one time, because probably they had not understood or simply forgot. Then I reminded them how very important their work was, and that I needed to see it to be able to help them with it. I also explained that if it happened again, they would have to sit and watch the other children play during that recess. (I did not want staying in the classroom to be a penalty, so I restricted their activity outside, instead.) Most years, just one new child would forget, and on just one occasion, a child had to sit twice before he got the idea. (I made sure they were at the Step easy enough for them, so I could know it was a matter of their simply forgetting to ask me to see their work.)

Requiring each child have their work checked before the end of the period gave me 3 opportunities to assess a child’s work. First was at #2 in the cycle, both when I worked with a few students at my table and later when I got up and circulated among the others still working. The second opportunity was when the children came to me to be checked at #3. The third time was at #5, when I could look through their writing books after school, which is why they left their books in a central location. But I seldom did that, because from my interaction with them at #2 and #3, I already had a good idea of who needed what from me the next day. (Regarding #4 in the illustration, I did not have the children sign off on a chart. But I included it in the illustration below as #4, because in my research in highly effective classrooms, I saw other teachers using such a chart instead of a concrete item such as my clothespin. But those teachers were asking their children to carry out additional tasks, usually something related to math, on a “must-do” chart, while I wanted my children only to be focused on writing during this period.)

I highly recommend either an object that’s collected as a “ticket” to recess, or a sign-off chart the teacher looks at and uses in the same way. This, as before I gave the children the responsibility for having their work checked, I was never sure exactly how things were going. I found that looking through their work after school didn’t accomplish what I wanted — as how much good did it do to leave it until then to discover that a child had not finished their work? So eventually, some sleepless nights convinced me I needed a way to be certain, on the spot. So it was a big relief to me to know instantly each morning that each child had actually successfully completed their work. This instant check, allowed me to keep a finger on the pulse of the entire class and intervene when it would do the most good — and making the students responsible for doing it was not only a good habit to instill in them, but it left me free to concentrate on other things, rather than watching to make sure everyone was going to finish work by the end of the period.

I also learned eventually that it was too difficult for me to try to “keep everything in my head,” as some teachers did. So I developed the simple forms for keeping track of all this that I provided previously.

For another way to envision how the children and I operated together, see A Day in the Life of an Individualized, Language Experience Classroom.

Effects of Multi-Task vs Single-Task Settings: The Psychological Benefit Of Sharing Control With Students

The active Writing Work Period creates a Multi-Task Setting, where students are working independently at their own pace. They may be walking, talking, writing, cutting, drawing, painting, or simply stopping to watch as someone else works. In a multi-task setting, where children are free to move about, actively selecting materials and working on a variety of different tasks in this way, work is relatively private. So it is difficult to judge one’s own work against the work others.

When the teacher is controlling the activity and interactions of an entire group it creates a Single-Task setting. Here the responses and performance are public, thus everyone can see who is doing well and who is not. To feel the difference, think of speaking at the head table of a banquet or being singled out while everyone else listens — compared with having lunch with one or two good friends. Consider how you feel talking within each of these settings, much less having to perform. In my own research, students had a pretty good idea of who was really excelling, but they also reported feeling good about their own standing: Virtually all students — even those who were progressing more slowly than the others — reported they were about the same or better than everyone else.)

Research on the effects of the different task settings shows that children benefit across the board — emotionally, socially and with self-image — when working primarily in a multi-task setting. Further, when predominantly in a multi-task setting, they have a greater tendency to cooperate with others, while predominantly in the single-task setting, competing cliques based on performance are more likely to form. And these tendencies have been found to remain ingrained in the children who spend more time in one task setting over the other — even when they change settings. For discussion of this and other social/emotional differences, see The Effects of a Single-task vs. A Multi-task Approach To Literacy: a Sociological View.

________

*I carried the clothespins with me in a half-apron, along with extra pens, so I could be anywhere in the room. Giving the children a simple wooden clothespin rather than a sticker or star might sound strange, but I wanted to be certain that it was seen as a signal they had finished their work and had it checked — not a reward. For research has shown (Maehr) that giving extrinsic rewards for high-level thinking activities can decrease motivation. (Rewards for low-level tasks, such as learning the multiplication tables or memorizing other things, does not appear to decrease motivation.)